All linked products are independently selected by our editors. If you purchase any of these products, we may earn a commission.

Back when I was in college in the 2010s, there was a de facto uniform for girls who wanted to signify wealth in their style of dress: a Cartier Love bracelet, a Gucci Horsebit loafer, and a bag I wasn’t familiar with. Despite growing up a fashion-obsessed teen, I didn’t recognize the brand behind that all-over printed tote — though I suspected a subsequent hefty price tag, given the context. I fell down quite the online rabbit hole in my attempts to find the origin of (and assign value to) this elusive accessory. Therein lies the magic of Goyard.

If you’re not yet familiar with the storied French leather goods house, you’re not alone: Its handbags, which retail for thousands of dollars and can’t be purchased online, are characterized by a lack of visible logos. (Instead, it favors a subtle but recognizable print.) Its know-how dates back to 1792, when Pierre-François Martin would manufacture trunks, boxes, and cases for the ultra wealthy, with clients ranging from the Romanovs to the Rockefellers. When François Goyard took over, he changed the name from Maison Martin to Maison Goyard in 1853.

Little has changed since, as the brand has become known for its timeless designs, rarely releasing new styles and highlighting its special “goyardine” canvas made of a secret combination of linen and cotton, which is then screen-printed to achieve the signature embossed pattern. And while Goyard has a website, it’s only to inform you of the product offering, not the prices. A tote bag starts around $1,600 — if you want a brand-new one, you must stand in line to enter one of its few physical locations in major cities like New York, Paris, and Tokyo to get it.

In the wake of trends that have grown into movements, like “quiet luxury” and “stealth wealth,” this exclusive buy-in is more desirable than ever. Christine Ellis — founder and CEO of Christine Ellis Associates, a luxury retail consultancy based in Milan — says it’s helped the established brand become even more relevant: “The luxury customer — I’m talking a real luxury customer who historically bought Hermès, Chanel, all these very high-end, exclusive brands — wants a bag that nobody else has.”

“If you look at the pillars of luxury,” notes freelance fashion writer and consultant Philippe Pourhashemi, “they’re exclusivity, quality, and rarity. Something cannot be luxurious if it’s not rare.”

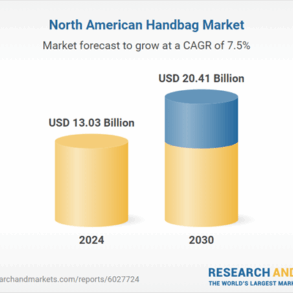

Goyard has always done well on the luxury resale platform Rebag, but, in 2024, it crept into the top 10 best-selling brands for the first time, sitting next to massive heritage brands like Louis Vuitton and Gucci. On average, its bags retain 104% of their value on the secondhand platform. With this, Goyard has reached a “unicorn status,” in which brands retain over 85% of their value on the secondhand market — a qualification shared only by Hermès, Chanel, and Louis Vuitton.

“Its products are practical,” says Rebag CMO Elizabeth Layne, who purchased the St. Louis tote when her children were babies. It started as her diaper bag, before transitioning to an everyday carryall: “It’s a workhorse bag.”

As luxury becomes more accessible thanks to social media and e-commerce — especially resale — owning a luxury bag is now a much more common experience. How, then, does one differentiate themselves in a crowded marketplace?

Like Hermès and Chanel, Goyard is privately owned: Jean-Michel Signoles acquired the company in 1998, and brought it back from ruin with an exclusivity-based business model. In 2009, he told the New York Times he “coveted this company for 20 years,” and spent years persuading them to sell. Signoles rarely does interviews, nor does he court press — neither does the brand, which spends very little, if anything, on advertising. (Its social media presence is relatively contained: It has just over a million followers on Instagram, whereas Hermès and Chanel boast 15 million and 60 million, respectively.) And because it’s not part of a luxury conglomerate, like Gucci or Louis Vuitton, it doesn’t have to publish its financials or justify creative decisions to a board or CEO juggling numerous other companies.

In the wake of massive price increases across the luxury industry, Goyard has left its largely untouched. In 2022, Louis Vuitton’s Neverfull retailed for $1,690; today, it goes for $2,030 — more than Goyard’s Saint Louis Tote, but less than its Anjou, for comparison. Ellis notes this is both a sign that Goyard’s business is doing well and a strategic ploy: the price increases alienate the middle-class consumer. Goyard’s quality-to-price value proposition is relatively strong, while other luxury brands have recently experienced criticism for declines in quality despite upticks in price.

“Consumers are much more aware of intrinsic value,” notes Pourhashemi. “There’s something about Goyard that, despite its success, still feels confidential. Today, that’s priceless, because a lot of consumers are suffering from luxury fatigue. They’re just tired of seeing the same old brands all the time.”

Still, these exclusivity tactics inevitably lead to a burgeoning resale market, as exhibited on Rebag. Though its Goyard client often skews older, styles like the Plumet clutch wallet — a style inspired by the pouches that come inside larger totes, introduced in 2018 — have resonated with not only a secondhand consumer but a younger generation as well. We’ve seen this on TikTok, where #goyard has 58.8K total posts and saw over a 90% increase in posts in the first 11 months of 2024, compared to 2023. (#luxury has 7.8M total posts, and saw almost a 30% increase between the first 10 months of 2024 when compared to the same time period in 2023.) Most mentions of the Plumet on the platform have been in 2024; on Rebag, it has experienced a 21% increase in value from 2023 to 2024, and boasts a 139% retention rate.

Despite these practical reasons for purchasing a Goyard bag, Pourhashemi doesn’t think something like resale value matters much to Goyard’s true target audience.

“Within the realm of luxury, you’re dealing more with longing, desire, emotions, passion,” he argues. “It’s something that you want to acquire because it represents something.”

Goyard wants to lure you into its stores to see, touch, and fall in love with the product — and perhaps contract a hand-painted monogram while you’re there.

“It does a very good job at delivering a personal service,” Pourhashemi says. “Luxury should be personal.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.