The exact timeline of dog domestication in China is still being determined, but archaeological sites between 6,000 and 10,000 years ago exhibit evidence of having domesticated dogs.

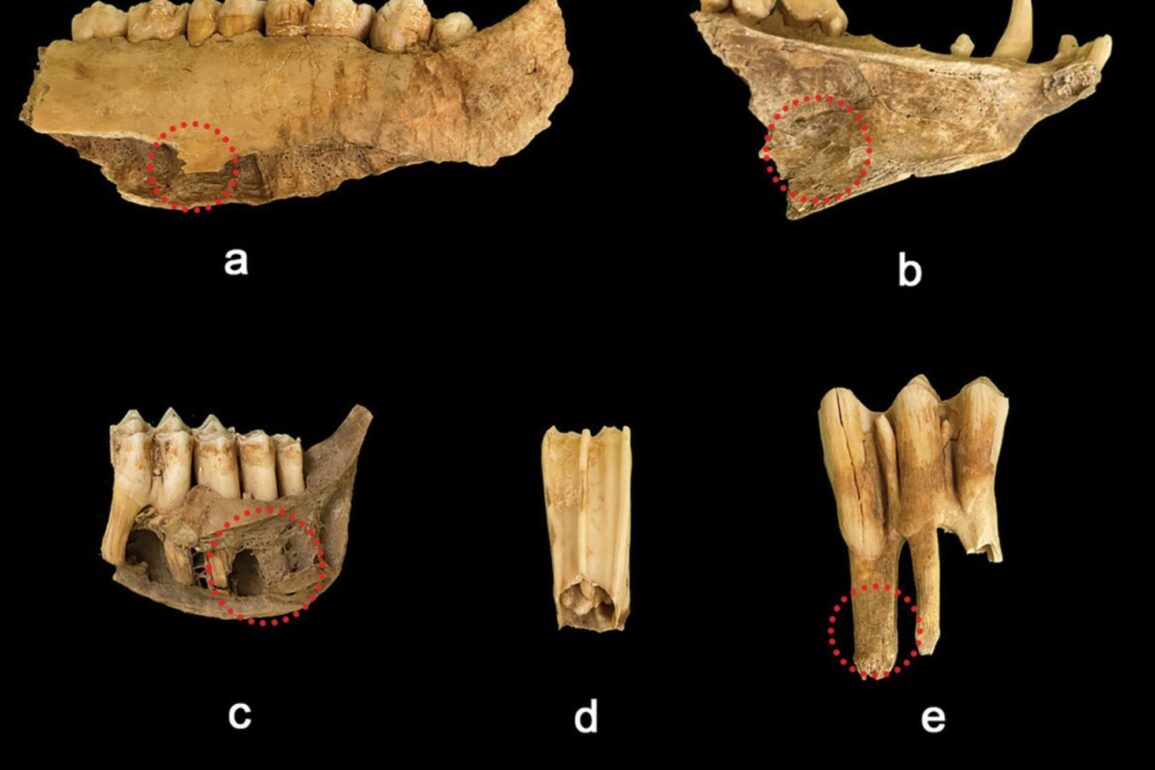

By analysing dental fossils from the Longshan communities at the Kangjia Neolithic excavation site in the central plains, scientists were able to determine that dogs likely survived on grains in the form of cooked food scraps.

While the idea of a grain-based diet may be a surprise to our popular imagination of ancient dogs, genetic testing suggests that dogs may have adapted to eating grains as far back as 30,000 years ago.

The Longshan people are famous for the emergence of advanced pottery during the Neolithic era, and the village at Kangjia is estimated to be between 4,000 and 4,500 years old. It was excavated in the 1980s and 1990s and included the discovery of 33 houses, nine human remains and countless domestic and wild animal bones.

The people likely cultivated farmlands of millet and rice while hunting for meat and wild resources. There is also evidence of human sacrifice at the Kangjia site, with one woman being dismembered before burial.

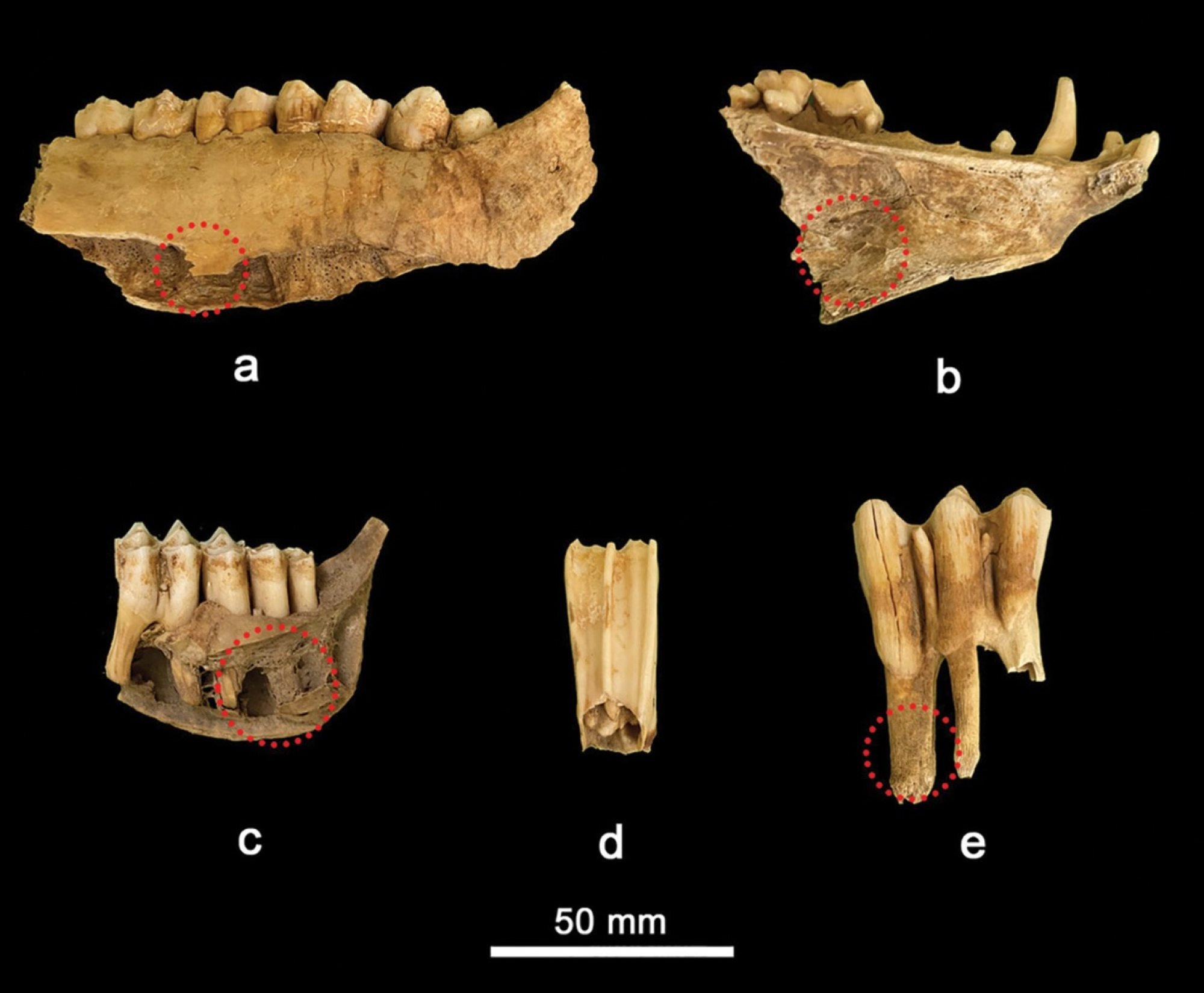

Researchers analysed the jaws of a variety of animals – pigs, sheep, goats, water buffaloes and even deer – and found evidence of starch remains on the teeth of the animals, indicating that they had subsisted on grains. Specifically, the dogs likely ate millet, wheat, rice and other grass-based foods.

Between the pigs and dogs, the scientists found 38 grain particles on the teeth that showed evidence of destruction from chewing or digestive bacteria. However, the discovery of 13 granules that exhibited evidence of cooking-related destruction led the researchers to conclude that the dogs likely subsisted on cooking scraps.

“At Kangjia, both pigs and dogs were domesticated as household animals. Pigs were the main source of animal protein for daily sustenance and ritual feasts. While dogs likely served various functions, including companionship, and were also consumed at Kangjia,” said Wang.

The team did indicate that, because of the small sample size, making broad pronouncements about the diets of animals that lived over 4,000 years ago is complicated.

Yet, by analysing stable isotopes, the team hypothesised that millet contributed between 65 and 85 per cent of the ancient dogs’ diets. They then proposed that other grass-based foods also made up a large chunk of the remaining consumption habits.

The researchers wrote that the prevalence of a wide range of domestic crops in the teeth analysis, including the prevalence of starch remains in wild animal remains, suggests the Longshan people of Kangjia “actively managed domestic animals and influenced the subsistence of wild animals.”

The Kangjia site is particularly notable for exhibiting evidence of a feasting culture, and the teeth analysis points to a sophisticated system for pig husbandry.

Much like today’s bovines, the teeth analysis indicates a diet of food scraps similar to modern “slop” often fed to pigs.

The pigs were likely key indicators of social status during these ancient times, as high-class people would enjoy pig feasts facilitated by their greater ability to keep pigs within a household setting rather than allowing the animals to roam freely.

The researchers hinted at the possibility that some of the Kangjia pigs were raised specifically for feasting rituals. Other research into the village suggests that meat was not a large part of the local diet, indicating that the pigs were raised specifically to eat on special occasions.

“Feasts serve as a means to cultivate and maintain social relationships. From the late Yangshao to Longshan culture, competitive feasting emerged at both household and community levels, often used to establish and reinforce social hierarchies. Such activities facilitate the rise of social distinctions,” said Wang.

This establishment of social inequalities, ritualistic feasts, and sophisticated animal control would eventually lay the foundation for China’s transition into the Bronze Age.

“Historical narratives usually attribute the course of events to conscious human actions, yet this is not always the way in which history itself unfolded.

“Sometimes other kinds of actors, such as animals, were also central to the historical process. At Kangjia, both domestic and wild animals were integral to social life, participating in ritual systems and contributing to subsistence practices,” said Wang.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.