PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) – Two dog deaths have been connected to a type of harmful algae that’s new to the Columbia River, Clark County Public Health officials warn.

The discovery of benthic algal mats in the Columbia River stems from a report in October of 2024, when someone reported their dog died after recreating on an island in the river according to Clark County Public Health.

Now, county officials are working across the state, and across the state border, to prevent future illnesses.

“This first came on our radar in October of 2024. I received a very unfortunate call from a woman reporting that her dog had died after recreating on the Columbia River,” Maggie Palomaki — an environmental health specialist with Clark County Public Health — said during a May 21 County Board of Health meeting.

“The dog had a very onset set of symptoms including, tremors, salivation, stumbling vomiting and then they died shortly after that at an emergency veterinarian’s office,” Palomaki explained, adding the exposure happened on Ackerman Island and the dog never swam in the water, mostly staying on the shore. However, the dog did have plant-like material in its stomach, which experts believe was a benthic algae mat.

Working with the Washington State Department of Health, Palomaki said experts found high levels of toxins in a sample from the dog’s stomach, noting the dog most likely died from cyanotoxin poisoning from toxic algae.

“The dog’s owner also experienced symptoms of numbness and tingling in the mouth and tongue believed to be from an exposure when they were providing rescue breaths to the dog, but they fully recovered,” Palomaki added. Officials said the dog’s owner was well-informed about the dangers of harmful algal blooms and there were visible blooms at the Port of Camas-Washougal, the Columbia River or Ackerman Island at the time.

Clark County Public Health already monitors harmful algal blooms — which are an overgrowth of algae in a body of water and can impact water quality.

HABs can produce toxins that are harmful to humans and animals, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and can appear as thick scum in the water, which thrives in warm, slow-moving water such as lakes or ponds. HABs often appear in a green, brown, red or blue color with a strong odor of decay.

“These have been very common in Clark County for quite a while,” Palomaki said.

Benthic algae mats, on the other hand, are an “emerging topic,” the environmental health specialist said.

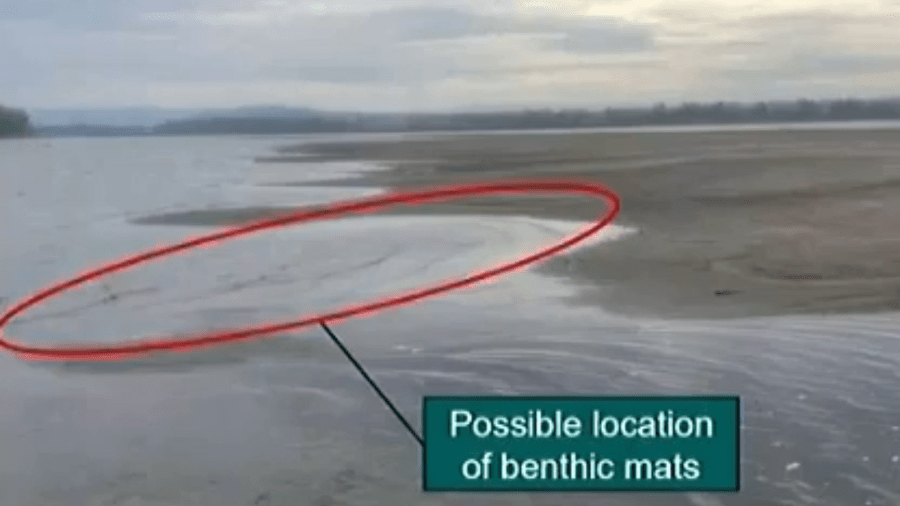

“Benthic algae mats are a different type of harmful algae. So, we first tested these in Clark County in October 2024. This is very new to us in public health,” Palomaki said. “Benthic algae mats, rather than being dispersed through the water column, they’re actually attached to the substrate at the bottom of a body of water.”

Because they are attached at the bottom of the water, Palomaki explained that mats can grow in fast- or slow-moving waters such as rivers and streams. The mats also do not impact water clarity as other HABs do.

After the reported death, Clark County Public Health visited the site in November 2024, where officials found a brown mat-like material at the water line. After the material was sent for analysis, health officials found elevated levels of toxins.

“We know this is happening on both sides of the river,” Palomaki said, explaining another dog death was reported after recreating in the St. Helens, Oregon area in August.

“In public health, our question now becomes: how did this happen?” Palomaki said. “First, benthic algae mats are just not familiar to the general public. We were not aware and had not received reports of this type of algae in Clark County waters until this event happened in 2024. So, this is new to all of us.”

“Following this tragic event, we immediately posted temporary educational signage at all 11 marinas and boat launches on the Columbia River,” Palomaki said, noting CCPH staffers have since been learning more about the algae.

Because the Columbia is a shared body of water, Palomaki said Clark County Public Health has been having monthly meetings with the Washington Department of Health, the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality and the Oregon Health Authority to discuss public health advisory strategies for the river.

As public health officials learn more about the algae, CCPH is warning people not to touch or ingest mats and to not let dogs eat or drink from water where mats could be present.

County health officials warn symptoms of toxic algae mat exposure in humans includes tinging, burning, drowsiness, salivating, difficulty speaking, vomiting and diarrhea. In some cases, exposure can be deadly to humans and can also cause liver failure, officials said.

In dogs, symptoms can include diarrhea, vomiting, unconsciousness, weakness, disorientation, difficulty breathing and excessive salivation.

People experiencing symptoms should contact their health care provider or poison control and pet owners should contact an emergency vet if their dog is experiencing symptoms or dies from possible exposure, Clark County Public Health says. Exposures and illnesses associated with the toxic algae should also be reported to Clark County Public Health or the Oregon Health Authority.

While Clark County Public Health has developed a public education strategy to prevent future exposures, there are still “ongoing challenges,” according to Palomaki – noting the Columbia River is very big and deep with miles of shoreline and islands to monitor.

Additionally, she warns toxin tests of water samples alone are not a good indicator for potential mats and the King County Environmental Lab – which tests samples for the toxins – is not set up to routinely test algae mats.

There is also no toxicity thresholds defined for benthic mat advisories in Washington, whereas planktonic HABs have thresholds established by the state. So, there’s no guideline for mat advisories, Palomaki said, noting the science isn’t there yet.

Along with these challenges, public health officials warn benthic algae mat cases could worsen with climate change.

“In terms of long-term prevention, algae like two things. They like nutrients and they like sun and warmth,” said Clark County Public Health Director Dr. Alan Melnick during the board meeting. “So, we may end up seeing more of these as the climate changes over time.”

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.