Abstract

Dogs play a crucial role in the transmission cycle of Trypanosoma cruzi and their presence in domicile increases the risk of infection in humans. In Yucatán, Mexico previous studies have reported T. cruzi infection in dogs from both rural and urban areas, which we expanded here, to better understand infection dynamics. A total of 186-dogs were screened for T. cruzi infection by PCR and serology. Parasite burden, genotype, immune response, cardiac alterations, and roaming behavior of the dogs were analyzed. The T. cruzi prevalence was 26.8% (50/186). Genotyping of T. cruzi revealed the predominance of TcI parasites, although most dogs (15/25, 60%) harbored mixed infections with additional DTUs including TcII, TcIV, TcV and TcVI. Antibodies against T. cruzi proteins were detected in > 90% of infected dogs, confirming their immunogenicity in natural infections. Mild ECG abnormalities were present in 40% of infected dogs. A logistic model suggested that the interplay between the host responses to multiple parasite strains could mediate differences in disease severity (P = 0.0002, R2 = 0.65). Finally, parasite diversity and dog roaming behavior support a role of dogs as an important link in T. cruzi transmission cycles among habitats. Together, these data provide a strong rationale to target dogs in integrated Chagas disease control interventions.

Introduction

Chagas disease is a parasitic disease caused by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi (T. cruzi) afflicting both humans and dogs. At least 6 million people are currently infected in Latin America1. In dogs, T. cruzi infection is highly prevalent in many countries such as Argentina, Mexico, Brazil and the US2,3,4. In Yucatan in southern Mexico, several studies on the prevalence of T. cruzi infection in dogs have reported values from 3.3 to 29.9% in rural communities, depending on the diagnostic test used and the locality5,6,7,8,9,10,while a prevalence of 12.2–34% in urban areas have been found based on serology, and to 17.3% based on PCR5,11.

Thus, dogs are considered to be good sentinel for the occurrence of domestic T. cruzi parasite transmission12,13,14and may increase the risk for human infection15,16. Dogs are also a common blood feeding sources for triatomine vectors17,18,19 and because bugs feeding on dogs also feed on multiple sylvatic hosts, dogs may act as a bridge between domestic and sylvatic transmission cycles of T. cruzi. Finally, dogs can develop acute and chronic infections with clinical similarities to human Chagas disease including cardiac abnormalities20,21,22,23. Thus, naturally infected dogs exhibit cardiac alterations such as ventricular arrhythmias, atrioventricular (AV) block24, sinusal block, right bundle branch block, QRS complex alterations4, or supraventricular premature contractions25. These cardiac alterations can lead to significant morbidity and mortality in dogs22,23, although the mechanisms underlying cardiac disease progression remain unclear.

Parasite strain diversity may be a contributing factor on its epidemiological, biological and medical characteristics26, as T. cruzi is divided into seven main lineages referred to as discrete typing units (DTUs), named TcI to TcVI, and TcBat27,28, with extensive biological diversity. However, while experimental infections with different strains have shown variable progression of the infection29,30,31,32,33, clear associations with parasite DTUs have not been uncovered. Nonetheless, more recent studies have highlighted the frequent occurrence of infections with multiple parasite strains in dogs34and many other mammalian hosts35,36,37, including humans38, suggesting that multiplicity of infection may be a contributing factor to disease progression. Indeed, the follow-up of naturally infected macaques indicated that multiple infections were rather associated with a lower parasitemia and limited cardiac disease progression, while infections with a low diversity of parasites resulted in higher parasitemia and progressive cardiac disease39. Host immune response is also likely involved in Chagas disease progression and a cellular immune response, and particularly the activation of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells is critical for the control of T. cruziinfection40,41.

Based on the above, it has been argued that dogs would be an excellent target for the control of Chagas disease, and interventions based on vaccination or the use of insecticide-impregnated collars/treatments have been proposed42,43,44,45,46. Nonetheless, such strategies require a more detail understanding of T. cruzi infection in dogs. Thus, the aim of this study was to characterize T. cruzi parasite burden, DTU lineage, cardiac alterations, immune response, and movement between habitats of dogs with natural infection in a rural village of Yucatan, Mexico. These observations can provide valuable insights for the evaluation of future control interventions targeting dogs.

Results

Prevalence and incidence T. cruzi natural infection in dogs

A total of 186 client-owned domestic dogs from the village of Sudzal, Yucatan, Mexico, were screened for T. cruzi infection by PCR and rapid-test serology. Parasite DNA was detected in 50/186 (26%) of dogs using PCR, and 73/186 (39%) using Stat-Pak rapid test (Table 1). Only 21/186 of samples (11.2%) tested positive with both PCR and the rapid test, indicating a high level of discordance among tests (Table 1). Infection rates did not differ between male and female dogs (X2 = 0.35, P = 0.55 for PCR, X2 = 0.06, P = 0.81 for Stat-Pak, and X2 = 2.69, P = 0.10 for PCR + Stat-Pak). Based on dog age, the incidence of T. cruzi infection was estimated at 6.2% per year by PCR, 5.6% per year by rapid test and 9.1% per year by both PCR and rapid test (Supplementary Fig. 1).

T. cruzi genotyping

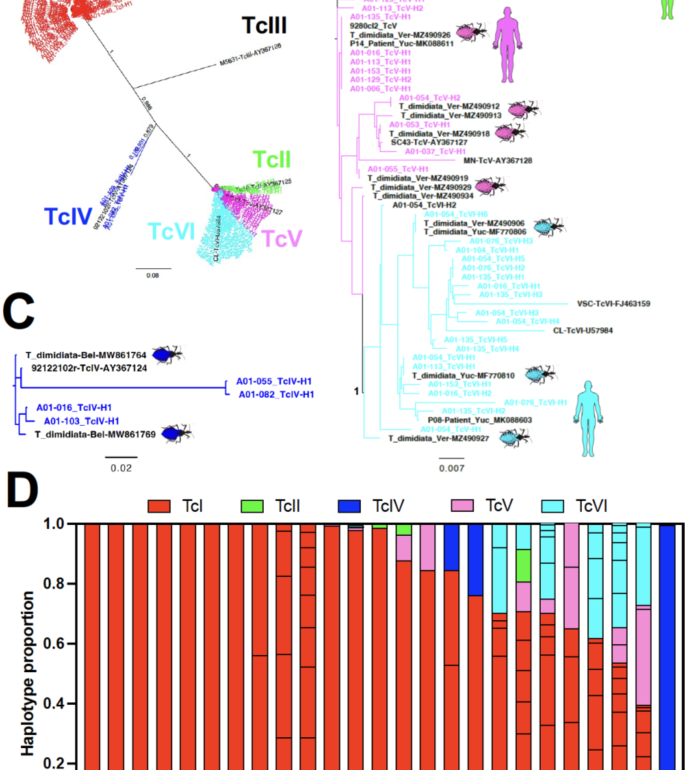

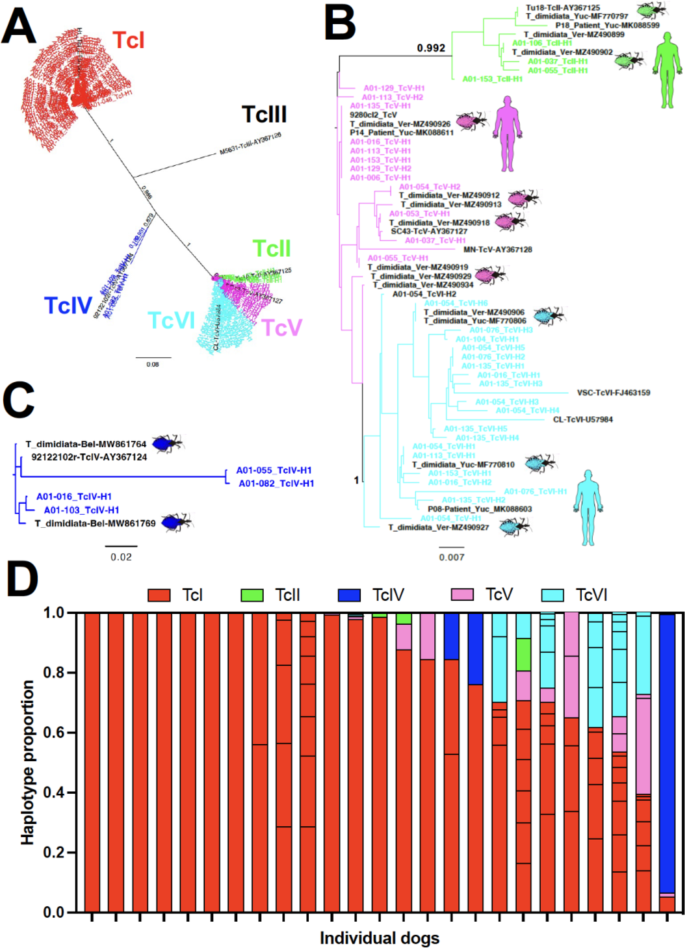

Genotyping of T. cruzi was achieved in 25/47 (53%) of PCR-positive dogs. While TcI largely predominated and was present in all infected dogs, TcII, TcIV, TcV and TcVI were also detected (Fig. 1A). Phylogenetic comparison of parasite sequences from dogs indicated a high similarity and a few identical sequences with sequences previously reported in Triatoma dimidiata vectors from several villages from Yucatan17and in parasites from Chagas disease patients in Yucatan38 (Fig. 1B and C). Both studies report the presence of multiple parasite DTUs, and some of the reported sequences were used in this study to compare with the sequences obtained from the dogs. Various haplotypes of TcI sequences were detected in 10/25 dogs (40%), while 15/25 dogs (60%) harbored infections with multiple DTUs including TcI, TcII, TcIV, TcV and TcVI in variable proportions (Fig. 1D).

Genotyping of T. cruzi from infected dogs. (A) Global phylogenetic analysis of all sequences from 25 infected dogs, using approximately maximum likelihood, indicating the presence of sequences from TcI, TcII, TcIV, TcV and TcVI DTUs. Sequences from each DTUs from dogs are color-coded as indicated (labeled A01-xxx_Tcx-Hx) and sequences from reference parasite strains are in black. Numbers on branches indicate bootstrap support. (B) Phylogenetic analysis of TcII, TcV and TcVI sequences from dogs (color-coded by DTUs) with previously reported sequences from vectors and patients from Mexico (in black). Numbers on branches/nodes indicate bootstrap support, shown only for values > 0.95 for clarity. (C) Phylogenetic analysis of TcIV sequences from dogs with previously reported sequences from vectors from Belize (in black). (D) Composition of infection in individual dogs. The relative proportion of haplotypes, color-coded by DTUs, is indicated for individual dogs.

Blood parasite burden

The parasite burden in blood samples from infected dogs was determined using qPCR. T. cruzi-infected dogs older than 12 years tended to harbor a higher parasite load, but this was largely due to two outlier dogs, and this did not reach statistical significance when these outliers were removed from the analysis (Fig. 2A). No significant differences in blood parasite burden were found between male and female dogs (Student t = 0.97, P = 0.34, Fig. 2B), nor according to parasite genotypes infecting dogs (Student t = 0.36, P = 0.71, Fig. 2C).

T. cruzi blood parasite burden. (A) Parasite burden and dog age. Parasite burden tended to increase with age, but this was due to 2 older outliers (continuous line, R2 = 0.28, P < 0.001), and this did not reach statistical significance when these 2 dogs were omitted (dotted line, R2 = 0.03, P = 0.26). (B) Parasite burden and dog sex. There was no significant difference according to sex (Student t = 0.97, P = 0.34). (C) Parasite burden and genotype. There was no significant difference according to genotype (Student t = 0.36, P = 0.71).

Immune response of naturally infected dogs

IgG response was determined through ELISA. Only 55.2% of all dogs presented a positive IgG response against T. cruzi soluble antigen (Fig. 3A), largely due to a relatively high background of cross-reactivity of negative samples. On the other hand, over 90% of dogs presented a positive response against Tc24-C4 and TSA1-C4 antigens (Fig. 3B), suggesting that these vaccine antigens are immunogenic during a natural infection. No significant differences were found in antibody levels according to sex (Student t = 0.46, P = 0.64; t = 0.77, P = 0.44; and t = 0.34, P = 0.74 for antibodies against soluble antigen, TSA1-C4 and Tc24-C4, respectively), age (ANOVA F = 0.36, P = 0.55; F = 0.27, P = 0.60; F = 0.1, P = 0.95, respectively), or parasite DTUs (Student t = 0.78, P = 0.44; t = 0.63, P = 0.53; and t = 1.05, P = 0.31, respectively). A recall response of T cells was evaluated by flow cytometry analysis of PBMCs from naturally infected dogs after in vitro stimulation with T. cruzi soluble antigens, TSA1-C4 and Tc24-C4 antigens. None of the T. cruzi antigens including Tc24-C4 and TSA1-C4 recombinant proteins were able to induce a significant recall response (Fig. 4).

IgG response of dogs with T. cruzi positive PCR. (A) IgG response against T. cruzi soluble antigen extract, indicating that 55.2% of dogs had parasite antibodies. (B) IgG response against vaccine antigens Tc24-C4 and TSA1-C4 in naturally infected dogs. >90% of dogs had antibodies against vaccine antigens. Dotted horizontal lines indicates cut-off for positive samples.

ECG abnormalities

Cardiac function was assessed using ECG recordings for 10 uninfected and 34 infected dogs. Sinus rhythm was observed in all dogs, characterized by the presence of a positive polarized P wave within lead II. No ECG alterations were detected in uninfected dogs, while 41% of T. cruzi-infected dogs presented some mild alterations (Table 2). The most frequent alteration detected in 32% of T. cruzi-infected dogs was a left electrical axis deviation, while 6% presented a first-degree AV block with a longer P-Q interval, and bradycardia was observed in 3% of infected dogs (Table 2). Importantly, dogs with high parasite burden were more likely to present cardiac alterations that those with low parasite burden (X2 = 4.9, d.f.=1, P = 0.02), Relative risk = 2.7 (95%CI 1.04–7.04), but there was no significant association with parasite genotype (X2 = 0.92, d.f.=1, P = 0.34).

Multivariate linear discriminant analysis (LDA) of ECG parameters further indicated a marked difference in ECG profiles between uninfected and infected dogs (PERMANOVA F = 3.64, P = 0.002), and 91% of dogs could be correctly reclassified based on their ECG parameters (Fig. 5A). When dogs were stratified according to a high/low T. cruzi parasite burden, additional differences in ECG parameters were detected by LDA (PERMANOVA F = 3.01, P < 0.001), and 75% of dogs could be correctly reclassified based on their ECG profile (Fig. 5B).

LDA of ECG parameters. (A) LDA of infected and uninfected dogs. A total of 91.1% of dogs could be correctly classified as T. cruzi infected/uninfected based on ECG parameters (PERMANOVA, F = 3.64, P = 0.002). (B) LDA of ECG parameters of dogs stratified according to their blood T. cruzi parasite burden. A total of 75% of dogs were correctly classified as with high, low parasite burden or uninfected based of ECG parameters (PERMANOVA, F = 3.01, P < 0.001).

To further assess potential relationships among parasite burden, parasite genotypes, immune response and cardiac alterations, we evaluated multivariate models. The best logistic regression model provided a very good prediction of blood parasite burden (high vs. low) based on parasite DTUs (TcI vs. mixed DTUs), TSA1-C4 IgG levels, and cardiac electrical axis angle (P = 0.0002, R2 = 0.65, receiver operating characteristics area under the curve ROC AUC = 0.96, Table 3). This suggested a likely functional association of the immune response, parasite genotypes and cardiac alterations.

Dog roaming behavior across habitats.

To assess dog roaming behavior, particularly in sylvatic areas, as a potential risk factor for T. cruzi infection and link between domestic and sylvatic parasite transmission cycles, a subset of uninfected and infected dogs were equipped with GPS collars to monitor their movement during five consecutive days/nights. There was extensive variability in dog behavior, with some dogs only roaming within 2–3 blocks from their home within the village, while others ventured outside the village for extended periods of time, likely with their owner when performing farmland work (Fig. 6A). Statistical analysis of the cumulative distance covered by dogs during the day or during the night reflected this high variability, and there was no significant difference in distance covered between uninfected and infected dogs (Mann Whitney U = 21, P = 0.53, Fig. 6B). Similarly, we calculated the proportion of time spent within the village or in sylvatic areas outside the village, which varied extensively and was similar for uninfected and infected dogs (Student t = 0.27, P = 0.78 during the day and Student t = 1.36, P = 0.20 during the night) (Fig. 6C). Thus, dogs spent about 10% of their total time outside the village, somewhat more during the day (12–15% of time) than during the night (3–10%).

Dog movement and T. cruzi infection. (A) Examples of dog movement during a 24 h period in the village of Sudzal. Movement during the day (pink track, 7 h –19 h) and during the night (yellow track, 19 h–7 h) are shown for uninfected and T. cruzi infected dogs. (B) Cumulative distance traveled during the day and night according to T. cruzi infection of dogs. (C) Percentage of time spent within the village or in sylvatic areas according to T. cruzi infection of dogs. Data are presented as mean ± SEM with individual dog data points averaging 5 days/nights recordings per dog (N = 6 for uninfected, N = 9 for T. cruzi infected).

Discussion

Dogs are thought to play a major role as domestic reservoirs of T. cruzi parasites increasing the risk of human infection, and potentially bridging domestic and sylvatic transmission cycles12,13,14,15,16,46,47, so that targeting dog infection as part of Chagas disease control interventions may help improve their efficacy. Indeed, a prevalence of T. cruzi infection between 10 and 30% has been observed across the Americas, even exceeding 50% in some areas48. In this study, we characterized in detail T. cruzi infection in client-owned dogs from the rural village of Sudzal, Yucatan, where previous studies had documented Triatoma dimidiata seasonal house infestation and human infection49,50,51, to provide a baseline for control interventions targeting dogs. We estimated a prevalence of T. cruzi infection of 26.9%, based on PCR, which is similar to the 29.9% previously reported6or the 34% by serology in dogs from urban areas52. It is also within the range of infection rates detected by serology in dogs from rural areas, which varies between 9.7–29.9%5,6,7,8,9,10. However, as has been reported previously2,53,54, there is a limited agreement among molecular and serological diagnostics, highlighting the need for improved simple tests for a reliable surveillance of infection in dogs. Parasite soluble antigens also resulted of limited sensitivity to detect T. cruzi infection (55%), while vaccine antigens Tc24-C4 and TSA1-C4 were recognized by > 90% of infected dogs. This confirmed that both parasite antigens are immunogenic during natural infection in dogs, and provide a strong rationale for their use as a vaccine against T. cruzi infection as suggested before44. Although no T cells response was detected, this finding may be somewhat limited by the lack of cytokine production analysis in T cells; as only the overall populations of CD3+, CD3+CD4+, and CD3+CD8+ cells were quantified. Importantly, assessing the production of Th1, Th2, and Th17 cytokines within these subpopulations would offer a more detailed understanding of the immune response.

Depending of the diagnostic criteria used, an annual incidence of 5.6 to 9.1% of new infections was observed, which is higher than the 3.8% previously reported in Texas-Mexico border55and 2.27% in Louisiana shelters53, evidencing that T. cruziis very actively circulating among dogs of rural Yucatan, Mexico, thus making them a valuable target for integrated Chagas disease control interventions that may include insecticide-treated collars or vaccination46.

Parasite burden in the peripheral blood was low but quantifiable, with similar levels as observed in other studies9,56, with no difference between male and female dogs, nor with dog age. In terms of parasite genetic diversity, the detection of a broad diversity of DTUs, although TcI predominated, is in agreement with previous studies in triatomine vectors and patients from Yucatan17,38and from other regions of Mexico, highlighting the diversity of strains circulating in the country18,57,58. Importantly, most dogs (15/25, 60%) harbored mixed infections with multiple DTUs including TcI, TcII, TcIV, TcV and TcVI in variable proportions. The high frequency of multiple infections observed in dogs is also consistent with previous reports in patients from the region38,and and in dogs34and other mammalian hosts35,37,39 from the southern US, suggesting that such multiple infections may be an important characteristics of many parasite transmission cycles. The diversity of strains detected further support the role of dogs as a bridge between domestic and sylvatic parasite transmission cycles, even though the origin of these parasite strains cannot be determined at this stage. Further studies characterizing T. cruzi parasite strains from other hosts species and specific habitats should help disentangle transmission cycles of the different DTUs in the region.

Analysis of ECG recordings indicated that naturally infected dogs presented mild electrical disturbances in comparison with dogs with experimental T. cruzi infection which may present more severe cardiac abnormalities including ventricular tachycardia, AV block, right bundle branch block (RBBB), ventricular arrhythmia or left bundle branch block25,44. Nonetheless, the ECG profile of naturally infected dogs presented significant changes that could be detected through LDA, compared to uninfected dogs, which may be indicative of early onset conduction defects, with the potential to progress towards more severe arrhythmias and heart failure over time. Remarkably, differences in ECG profiles could also be observed according to blood parasite burden, suggesting its potential relationship in disease progression. Indeed, our logistic model further included parasite DTU composition, TSA1-C4 IgG levels and QRS wave duration as predictors of blood parasite burden, with a high accuracy, strengthening the concept that the interplay between the host responses to multiple parasite strains mediates differences in disease progression, as hypothesized before39.

Finally, analysis of dog movement indicated that they spend about 10% of their time in sylvatic areas outside the village, with no significant differences in roaming behavior between infected and uninfected dogs. This observation suggests that dog behavior is not a major risk factor for T. cruzi infection, although this behavior may vary during the year, particularly if associated with farming activities of dog owners. Furthermore, it confirms that it is possible for at least some infections to occur in sylvatic areas, where risks of dog-triatomine contacts may differ from the domestic habitat. This, added to the high dispersal of T. dimidiata vectors previously described in the region59,60, is in agreement with dogs playing an important role as a bridge for T. cruzi transmission among habitats in rural Yucatan.

In conclusion, we identified in this study a high prevalence and incidence of T. cruzi infection in client-owned dogs from a rural village in Yucatan, Mexico. Most dogs (60%) harbored mixed infections with multiple DTUs including TcI, TcII, TcIV, TcV and TcVI in variable proportions, although TcI was often predominant. Mild ECG alterations were detected in about 40% of dogs. While parasite diversity could not be directly associated with differences in immune response, parasite burden or ECG alterations, a logistic model including some of these variables suggested that the interplay between the host responses to multiple parasite strains could mediate differences in disease progression. Finally, parasite diversity and dog roaming behavior support a role of dogs as an important link in T. cruzi transmission cycles among habitats. Together, these data provide a strong rationale to target dogs in integrated Chagas disease control interventions.

Methods

Diagnostic of T. cruzi infection

The study and procedures were approved by the Institutional Bioethics Committee (No CEI-05–2021) in strict compliance with NOM-062-ZOO-1999. All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. This study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines. The study was conducted in the village of Sudzal (20.87°N, 88.98°W) in Yucatan, Mexico, where we have been working for several years. This rural community has about 1,600 inhabitants, distributed in about 400 households and an estimated dog population of 300–500. Following written inform consent from dog owners, blood samples from a convenience sample 186 domestic dogs were collected and stored at −20°C until use. All dogs were tested for T. cruziinfection by PCR53,61. Briefly, DNA was isolated from 300µL of blood using Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification Kit (PROMEGA) following manufacture instructions. Genomic DNA was eluted in 50 µL of endonuclease-free water for PCR and qPCR. The primers TcZ1 (5’-dCGAGCTTCTTGCCCACACGGGTGCT-3’) and TcZ2 (5’-dCCTCCAAGCAGCGGATAGTTCAGG-3’) target a 188 bp nuclear repetitive microsatellite of T. cruzi61. Amplifications were performed using a T100TM thermocycler (Biorad, Hercules, CA, USA) in a volume of 12.5 µl containing 50 ng of DNA, 0.5 µL of each primer, and 6.25 µl of 2× DreamTaq Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The cycling parameters were an initial denaturation step at 94 °C for 3 min; 40 cycles at 94 °C (45 s), 57 °C (1 min), and 72 °C (10 min); and a 10 min final extension at 72 °C. Positive (purified T. cruzi DNA) and negative (ultrapure H2O) controls were included for each PCR. After amplification, PCR products were separated by electrophoresis on a 1.0% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide and visualized by UV transillumination. For serological evaluation, a rapid immunochromatographic test CHAGAS Stat-pak (Chembio, NY) was also run on all samples53.

T. cruzi genotyping

Parasite genotyping was performed on all PCR positive samples by next-generation sequencing of the mini-exon gene marker as described before34,62, to assess DTU and intra-lineage diversity. Briefly, mini exon sequences were PCR amplified with TrypMe3 and TccH primer set, along with Tc1, Tc2 and Tcc primers63. The amplified products were then purified and pooled for each sample, followed by library preparation and sequencing on an Illumina MiSeq platform at a depth of 90,000–500,000 reads/samples. The reads were competitively mapped to T. cruzi mini-exon reference sequences representing all seven parasite DTUs using Geneious Prime 2024 software. The mapped sequences were trimmed of PCR primer sequences and realigned using the MAFFT subroutine implemented in Geneious. The FreeBay single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)/variant tool64 was used to identify sequence variants and their frequencies, based on read abundance. Phylogenetic trees were constructed with FastTree 2.1.11 with the Jukes-Cantor models of nucleotide evolution. The reliability of each split in the tree is based on local support values with the Shimodaira-Hasegawa test and resampling the site likelihoods 1,000 times. Reference sequences covering DTUs TcI to TcVI from strains H1-YUC TcIa (EF576846), SylvioX10cl1 Tcld (CP015667), M5631 TcIII (AY367126), CL TcVI (U57984), SC43 TcV (AY367127.1), Tu18 TcII (AY367125.1), and 92122102r TcIV (AY367124) were used for the analysis. Further comparison of T. cruzi sequences from dogs with parasite sequences from triatomine vectors17and patients38 from the region was performed for TcIV, TcV, TcVI and TcII DTUs.

T. cruzi parasite burden

The blood parasite burden was measured with a standardized duplex qPCR method based on Taq-Man probes, targeting T. cruzi SatDNA and RNAse P gene as an internal amplification control65. Briefly, amplifications were performed with 5 µL of DNA in a final volume of 20 µL. Uracil-DNA Glycosylase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to the reaction mix, as a carry-over contamination control, and TaqMan RNase P Control Reagents Kit (Applied Biosystems) was used. Cycling conditions were as follows: a first step of 2 min at 50 °C and a second step of 10 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s and 58 °C for 1 min. All samples were analyzed in duplicate. The qPCR results were converted to parasitic load (parasite equivalents/mL of blood) using a standard calibration curve, and data were log-transformed for statistical analysis.

IgG response

Antibody levels were assessed in plasma samples using ELISA. Plates were coated with T. cruzi parasite lysate (H1 strain, TCI), Tc24-C4 and TSA1-C4 antigens (20 µg/mL, also from TcI) and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The plates were blocked with 1% BSA-PBST for two hours. After washes with PBST, plasma samples were added at 1:50 dilution and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. An anti-dog IgG conjugated with phosphatase (Applied Biological Materials Inc. Canada) was added at 1:4000 dilution for 1 h. Finally, a substrate solution containing p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) buffer was added to reveal the color. Optical densities (O.D.) were read at 405 nm using spectrophotometer.

Flow cytometry

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were obtained from T. cruzi infected dogs and stimulated with T. cruzi lysate, T. cruzi recombinant proteins TSA1-C4 and Tc24-C4, and RPMI medium as unstimulated control. Approximately 8 mL of blood was collected in heparinized tubes (Vacutainer, BD) and diluted 1:1 with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at pH 7.4 with Ca2+ and Mg+. The mononuclear cell layer was isolated using a density gradient of Ficoll-histopaque- 1.0771(Sigma, USA). Fresh PBS/heparinized blood was added to the Ficoll-histopaque solution in a 2:1 proportion and centrifuged at 400 x g for 40 min. PBMCs were collected, washed twice with PBS pH 7.4, and resuspended in complete RPMI-1640 medium (RPMIc) (Gibco, USA) containing antibiotics, non-essential amino acids, and 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS). After stimulation, the cells were collected, washed twice with PBS, and stained for T cell phenotyping using APC Mouse anti-Dog Pan T-cell (clone LSM 8.358.1.1), PE Mouse anti-dog CD4 (clone LSM 12.125), and FITC anti-dog CD8 (clone LSM 1.140) conjugated antibodies (BD, San Jose CA, USA) for 20 min at 4ºC. The cells were collected, washed twice, and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. 50,000 events were acquired using a FACSVerse Cytometer (BD, San Jose CA, USA) and analyzed using FlowJo_V10 software. The proportion of PBMCs identified as CD3+, CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+ T cells was calculated.

Electrocardiograms

The electrocardiograms (ECGs) were obtained by placing clips on the medial knee and elbows of the dogs. The paper speed was set to 50 mm/s, and the amplitude was set to 10 mm/mV on a ECG100G-VET electrocardiograph. A methodological and systematic approach was followed to interpret the ECGs, and determination of heart rate, rhythm, amplitude, and duration of the electrocardiographic waves66. At least four P-QRS-T complexes were registered for every 6 leads and 20 P-QRS-T complexes in lead II. The dogs were placed in right lateral recumbence during the procedure without sedation. Various parameters were measured in derivation II, including the amplitudes (in mV) of P, R, and T waves, duration in ( s) of waves and intervals including QRS complex, PR and QT intervals, as well as the mean electrical axis (MEA) determined in derivations I and III66. The normal MEA values on the frontal plane range between + 40º and + 100º. A right and left shift deviation occurred when the MEA was below and above the normal range respectively. An AV block was considered when the PR interval was > 0.13s.

Tracking of dog movements

Dogs were equipped with collars including a portable GPS data logger (igotU GT-120) programmed to record position data every 5 min as dogs followed normal activities. Collars were then removed to download GPS data for analysis. A total of 9 T. cruzi positive and 6 uninfected dogs were followed for 5 continuous days/nights during summer months (June-July). Timed position data were imported into QGis 3 to elaborate maps of individual dog movements. The cumulative distance traveled during the day (7 h –19 h) and night (19 h–7 h) was calculated for each dog and averaged for the 5 days/nights of recording. Similarly, the proportion of time spent within the village or outside the village (sylvatic area) was calculated for the day and night periods, and averaged for the 5 days/nights of recording for each dog. Infected and uninfected dogs were compared to assess potential differences in movements.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were summarized as mean/median ± SEM and were compared among groups with Kruskal-Wallis test or one-way ANOVA, or with Mann Whitney U or Student t test as appropriate, and categorical data were compared with X2. Differences among groups were considered significant when the P values were < 0.05. Graphs were generated with GraphPad-Prism 9.4.1 software. For the estimation incidence of infection, the changes in infection prevalence (measured by PCR, rapid test or both) with dog age were fitted by linear or semi-log regressions and the goodness-of-fit was assessed by R2. The slope corresponding to the increase in prevalence per year was used to estimate incidence, under the assumption of a stable transmission dynamic over time53. For multivariate analysis of ECG profiles, all ECG parameters were integrated into a LDA and compared according to the first and second discriminant axis according to infection status or parasite load classified as high/low. One-way permutation ANOVA (PERMANOVA) was used to assess the statistical significance of differences among groups with 10,000 permutations. The confusion matrix of the LDA analysis was also used to evaluate the accuracy of the reclassification of individual dogs among groups based on the similarities/differences in their ECG patterns and parasite load. Finally, logistic regression models predicting blood parasite burden (high/low) based on parasite genotypes (TcI only or mixed DTUs), immunological variables (IgG levels and T cell proportions), and ECG parameters (wave amplitudes and durations) were elaborated with different combinations of variables, followed by model selection based on Akaike information criteria, R2 and receiver operating characteristics area under the curve (ROC AUC).

Data availability

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in NCBI Genbank database under accession numbers PQ365783-PQ365887. The sequences will be available for public access within a few days.

References

-

WHO(World-Health-Organization). Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis)., (2024). https://www.who.int/health-topics/chagas-disease#tab=tab_1

-

Meyers, A. C., Meinders, M. & Hamer, S. A. Widespread Trypanosoma Cruzi infection in government working dogs along the Texas-Mexico border: discordant serology, parasite genotyping and associated vectors. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 11, e0005819 (2017).

-

Bradley, K. K., Bergman, D. K., Woods, J. P., Crutcher, J. M. & Kirchhoff, L. V. Prevalence of American trypanosomiasis (Chagas disease) among dogs in Oklahoma. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 217, 1853–1857 (2000).

-

Cruz-Chan, J. V. et al. Immunopathology of natural infection with Trypanosoma Cruzi in dogs. Vet. Parasitol. 162, 151–155 (2009).

-

Jimenez-Coello, M. et al. American trypanosomiasis in dogs from an urban and rural area of Yucatan, Mexico. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 8, 755–762 (2008).

-

Carrillo-Peraza, J. et al. Estudio serológico de La tripanosomiasis Americana y factores asociados En Perros de Una Comunidad rural de Yucatán, México. Arch. De Med. Vet. 46, 75–81 (2014).

-

Longoni, S. S. et al. An iron-superoxide dismutase antigen-based serological screening of dogs indicates their potential role in the transmission of cutaneous leishmaniasis and trypanosomiasis in Yucatan, Mexico. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 11, 815–821 (2011).

-

Reyes-Novelo, E. et al. Exposure to Trypanosoma Cruzi and Leishmania parasites in dogs from a rural locality of Yucatan, Mexico. A serological survey. Veterinary Parasitology: Reg. Stud. Rep. 44, 100911 (2023).

-

Chan-Pérez, J. I. et al. Combined use of Real-Time PCR and serological techniques for improved surveillance of chronic and acute American trypanosomiasis in dogs and their owners from an endemic rural area of Neotropical Mexico. Curr. Res. Parasitol. Vector-Borne Dis. 2, 100081 (2022).

-

Ortega-Pacheco, A. et al. Serological survey of Leptospira interrogans, Toxoplasma gondii and Trypanosoma Cruzi in free roaming domestic dogs and cats from a marginated rural area of Yucatan Mexico. Veterinary Med. Sci. 3, 40–47 (2017).

-

Jiménez-Coello, M., Acosta-Viana, K., Guzmán-Marín, E., Bárcenas-Irabién, A. & Ortega-Pacheco, A. American trypanosomiasis and associated risk factors in owned dogs from the major City of Yucatan, Mexico. J. Venom. Anim. Toxins Including Trop. Dis. 21, 1–4 (2015).

-

Lauricella, M. A., Castañera, M., Gürtler, R. E. & Segura, E. Immunodiagnosis of Trypanosoma Cruzi (Chagas’ disease) infection in naturally infected dogs. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 93, 501–507 (1998).

-

Castillo-Neyra, R. et al. The potential of canine sentinels for reemerging Trypanosoma Cruzi transmission. Prev. Vet. Med. 120, 349–356 (2015).

-

Tenney, T. D., Curtis-Robles, R., Snowden, K. F. & Hamer, S. A. Shelter dogs as sentinels for Trypanosoma Cruzi transmission across Texas. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 20, 1323 (2014).

-

Crisante, G., Rojas, A., Teixeira, M. M. & Anez, N. Infected dogs as a risk factor in the transmission of human Trypanosoma Cruzi infection in Western Venezuela. Acta Trop. 98, 247–254 (2006).

-

Gürtler, R. et al. Domestic dogs and cats as sources of Trypanosoma Cruzi infection in rural Northwestern Argentina. Parasitology 134, 69–82 (2007).

-

Dumonteil, E. et al. Detailed ecological associations of triatomines revealed by metabarcoding and next-generation sequencing: implications for triatomine behavior and Trypanosoma Cruzi transmission cycles. Sci. Rep. 8, 4140 (2018).

-

Murillo-Solano, C. et al. Diversity of Trypanosoma Cruzi parasites infecting Triatoma dimidiata in central Veracruz, Mexico, and their one health ecological interactions. Infect. Genet. Evol. 95, 105050 (2021).

-

Polonio, R., López-Domínguez, J., Herrera, C. & Dumonteil, E. Molecular ecology of Triatoma dimidiata in Southern Belize reveals risk for human infection and the local differentiation of Trypanosoma Cruzi parasites. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 108, 320–329 (2021).

-

Andrade, Z. A. et al. The indeterminate phase of Chagas’ disease: ultrastructural characterization of cardiac changes in the canine model. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 57, 328–336 (1997).

-

Caldas, I. S. et al. Parasitaemia and parasitic load are limited targets of the aetiological treatment to control the progression of cardiac fibrosis and chronic cardiomyopathy in Trypanosoma cruzi-infected dogs. Acta Trop. 189, 30–38 (2019).

-

Saunders, A. et al. Bradyarrhythmias and pacemaker therapy in dogs with Chagas disease. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 27, 890–894 (2013).

-

Meyers, A. C., Edwards, E. E., Sanders, J. P., Saunders, A. B. & Hamer, S. A. Fatal Chagas myocarditis in government working dogs in the Southern united States: Cross-reactivity and differential diagnoses in five cases across six months. Veterinary Parasitology: Reg. Stud. Rep. 24, 100545 (2021).

-

Meyers, A. C., Hamer, S. A., Matthews, D., Gordon, S. G. & Saunders, A. B. Risk factors and select cardiac characteristics in dogs naturally infected with Trypanosoma Cruzi presenting to a teaching hospital in Texas. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 33, 1695–1706 (2019).

-

Meyers, A. C. et al. Selected cardiac abnormalities in Trypanosoma Cruzi serologically positive, discordant, and negative working dogs along the Texas-Mexico border. BMC Vet. Res. 16, 1–12 (2020).

-

Tibayrenc, M., Barnabé, C. & Telleria, J. Reticulate evolution in trypanosoma Cruzi: medical and epidemiological implications. Am. Trypanosomiasis, 475–488 (2010).

-

Zingales, B. Trypanosoma Cruzi genetic diversity: something new for something known about Chagas disease manifestations, serodiagnosis and drug sensitivity. Acta Trop. 184, 38–52 (2018).

-

Zingales, B. et al. A new consensus for Trypanosoma Cruzi intraspecific nomenclature: second revision meeting recommends TcI to TcVI. Memórias Do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 104, 1051–1054 (2009).

-

Quijano-Hernández, I. A. et al. Evaluation of clinical and immunopathological features of different infective doses of Trypanosoma cruzi in dogs during the acute phase. The Scientific World Journal 635169 (2012). (2012).

-

Carneiro, C. M. et al. Differential impact of metacyclic and blood trypomastigotes on parasitological, serological and phenotypic features triggered during acute Trypanosoma Cruzi infection in dogs. Acta Trop. 101, 120–129 (2007).

-

Machado, E. et al. A study of experimental reinfection by Trypanosoma Cruzi in dogs. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 65, 958–965 (2001).

-

Morris, S. A. et al. Myocardial beta-adrenergic adenylate cyclase complex in a canine model of Chagasic cardiomyopathy. Circul. Res. 69, 185–195 (1991).

-

Duz, A. L. C. et al. The TcI and TcII Trypanosoma Cruzi experimental infections induce distinct immune responses and cardiac fibrosis in dogs. Memórias Do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 109, 1005–1013 (2014).

-

Dumonteil, E. et al. Genetic diversity of Trypanosoma Cruzi parasites infecting dogs in Southern Louisiana sheds light on parasite transmission cycles and serological diagnostic performance. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 14, e0008932 (2020).

-

Dumonteil, E. et al. Shelter cats host infections with multiple Trypanosoma Cruzi discrete typing units in Southern Louisiana. Vet. Res. 52, 1–8 (2021).

-

Pronovost, H. et al. Deep sequencing reveals multiclonality and new discrete typing units of Trypanosoma Cruzi in rodents from the Southern united States. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 53, 622–633 (2020).

-

Majeau, A. et al. Genetic diversity of Trypanosoma Cruzi infecting raccoons (Procyon lotor) in two metropolitan areas of Southern Louisiana: implications for parasite transmission networks. Parasitology 150, 374–381 (2023).

-

Villanueva-Lizama, L., Teh-Poot, C., Majeau, A., Herrera, C. & Dumonteil, E. Molecular genotyping of Trypanosoma Cruzi by next-generation sequencing of the mini-exon gene reveals infections with multiple parasite discrete typing units in Chagasic patients from Yucatan, Mexico. J. Infect. Dis. 219, 1980–1988 (2019).

-

Dumonteil, E. et al. Intra-host Trypanosoma Cruzi strain dynamics shape disease progression: the missing link in Chagas disease pathogenesis. Microbiol. Spectr. 11, e04236–e04222 (2023).

-

Bustamante, J. & Tarleton, R. Reaching for the holy Grail: insights from infection/cure models on the prospects for vaccines for Trypanosoma Cruzi infection. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 110, 445–451 (2015).

-

Kumar, S. & Tarleton, R. L. The relative contribution of antibody production and CD8 + T cell function to immune control of Trypanosoma Cruzi. Parasite Immunol. 20, 207–216 (1998).

-

Flores-Ferrer, A., Waleckx, E., Rascalou, G., Dumonteil, E. & Gourbière, S. Trypanosoma Cruzi transmission dynamics in a synanthropic and domesticated host community. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 13, e0007902 (2019).

-

Reithinger, R., Ceballos, L., Stariolo, R., Davies, C. R. & Gürtler, R. E. Chagas disease control: deltamethrin-treated collars reduce Triatoma infestans feeding success on dogs. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 99, 502–508 (2005).

-

Quijano-Hernández, I. A. et al. Preventive and therapeutic DNA vaccination partially protect dogs against an infectious challenge with Trypanosoma Cruzi. Vaccine 31, 2246–2252 (2013).

-

Fiatsonu, E., Deka, A. & Ndeffo-Mbah, M. L. Effectiveness of systemic insecticide dog treatment for the control of Chagas disease in the tropics. Biology 12, 1235 (2023).

-

Travi, B. L. Considering dogs as complementary targets of Chagas disease control. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 19, 90–94 (2019).

-

Mott, K. E. et al. Trypanosoma Cruzi infection in dogs and cats and household seroactivity to T. Cruzi in a rural community in Northeast Brazil. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 27, 1123–1127 (1978).

-

Strube, C. & Mehlhorn, H. Dog Parasites Endangering Human Health294 (Springer Nature Switzerland, 2021).

-

Dumonteil, E. et al. Eco-bio-social determinants for house infestation by non-domiciliated Triatoma dimidiata in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7, e2466 (2013).

-

Gamboa-León, R. et al. Seroprevalence of Trypanosoma Cruzi among mothers and children in rural Mayan communities and associated reproductive outcomes. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 91, 348 (2014).

-

Moo-Millan, J. I. et al. Disentangling Trypanosoma Cruzi transmission cycle dynamics through the identification of blood meal sources of natural populations of Triatoma dimidiata in Yucatán, Mexico. Parasites Vectors. 12, 1–11 (2019).

-

Jiménez-Coello, M., Guzmán‐Marín, E., Ortega‐Pacheco, A. & Acosta‐Viana, K. Serological survey of American trypanosomiasis in dogs and their owners from an urban area of Mérida Yucatán, México. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 57, 33–36 (2010).

-

Elmayan, A. et al. High prevalence of Trypanosoma Cruzi infection in shelter dogs from Southern Louisiana, USA. Parasites Vectors. 12, 1–8 (2019).

-

Curtis-Robles, R. et al. Epidemiology and molecular typing of Trypanosoma Cruzi in naturally-infected Hound dogs and associated triatomine vectors in Texas, USA. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 11, e0005298 (2017).

-

Garcia, M. N. et al. One health interactions of Chagas disease vectors, canid hosts, and human residents along the Texas-Mexico border. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 10, e0005074 (2016).

-

Enriquez, G. F. et al. High levels of Trypanosoma Cruzi DNA determined by qPCR and infectiousness to Triatoma infestans support dogs and cats are major sources of parasites for domestic transmission. Infect. Genet. Evol. 25, 36–43 (2014).

-

Izeta-Alberdi, A. et al. Trypanosoma Cruzi in Mexican Neotropical vectors and mammals: wildlife, livestock, pets, and human population. Salud Pública De México. 65, 114–126 (2023).

-

García-López, C. et al. Identification of discrete typing units of Trypanosoma Cruzi isolated from domestic environments in southeastern Mexico. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 24, 172–176 (2024).

-

Dumonteil, E. et al. Assessment of Triatoma dimidiata dispersal in the Yucatan Peninsula of Mexico by morphometry and microsatellite markers. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 76, 930–937 (2007).

-

Barbu, C., Dumonteil, E. & Gourbiere, S. Characterization of the dispersal of non-domiciliated Triatoma dimidiata through the selection of spatially explicit models. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 4, e777 (2010).

-

Moser, D. R., Kirchhoff, L. V. & Donelson, J. E. Detection of Trypanosoma Cruzi by DNA amplification using the polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27, 1477–1482 (1989).

-

Majeau, A., Herrera, C. & Dumonteil, E. An improved approach to trypanosoma Cruzi molecular genotyping by next-generation sequencing of the mini-exon gene. T Cruzi Infection: Methods Protocols, 47–60 (2019).

-

Souto, R. P., Fernandes, O., Macedo, A. M., Campbell, D. A. & Zingales, B. DNA markers define two major phylogenetic lineages of Trypanosoma Cruzi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 83, 141–152 (1996).

-

Garrison, E. & Marth, G. Haplotype-based variant detection from short-read sequencing. ArXiv 1207 (2016).

-

Cafferata, M. L. et al. Short-course benznidazole treatment to reduce Trypanosoma Cruzi parasitic load in women of reproductive age (BETTY): a non-inferiority randomized controlled trial study protocol. Reproductive Health. 17, 1–23 (2020).

-

Santilli, R., Moise, N., Pariaut, R. & Perego, M. Electrocardiography of the dog and cat. (2018).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.A.C.Q., J.V.C.C., E.D. developed the conceptual framework, designed the research, design, analysis and interpretation of data, substantively revised the manuscript. J.A.C.Q., M.J.E.T., C.F.T.P., M.N.C.C., P.P.M.V., L.M.P.P., V.M.D.H.: performed the experiments, substantively revised the manuscript E.W., L.E.V.L., J.O.L.: conception, design, substantively revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript and approved the final submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Calderón-Quintal, J.A., Escalante-Talavera, M.J., Teh-Poot, C.F. et al. Natural infection of Trypanosoma Cruzi in client-owned-dogs from rural Yucatan, Mexico.

Sci Rep 15, 10263 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92176-5

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-92176-5

Keywords

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.