Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

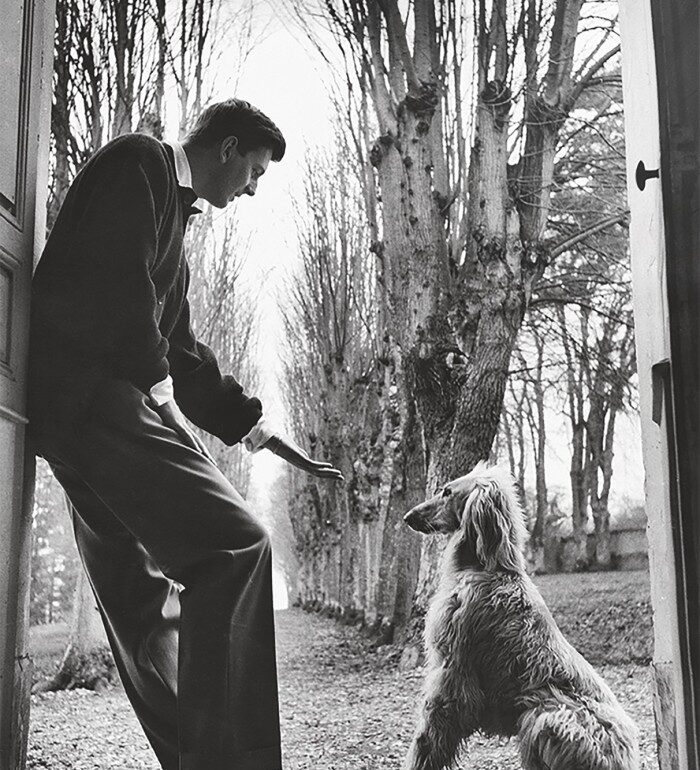

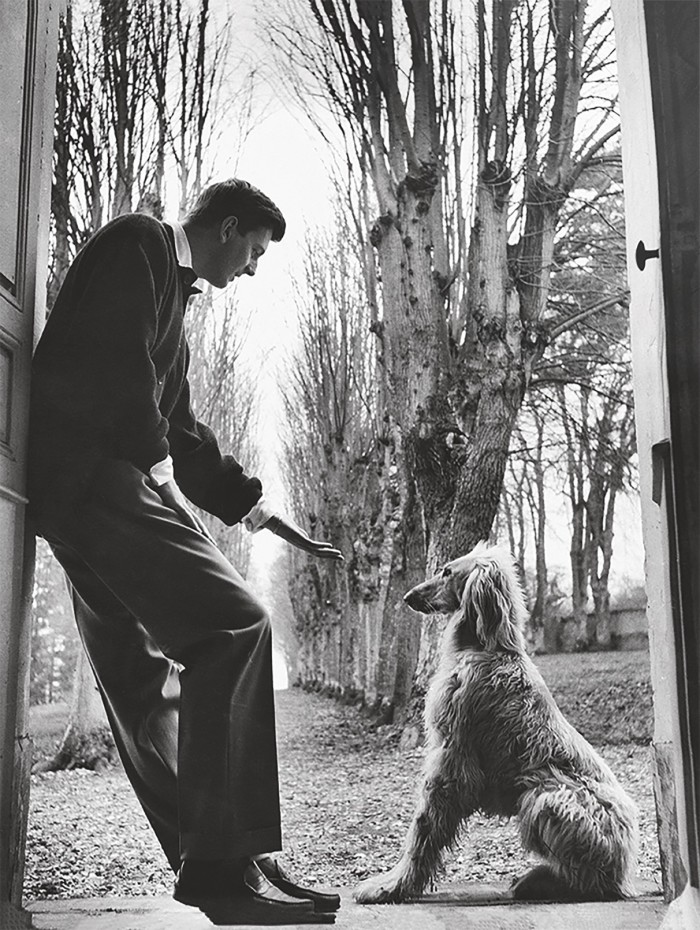

There is no such thing as a problem understood in isolation. I once had a 70kg wolfdog hybrid, Brenin, who would eat his way through the walls if I left him alone. That was a problem, but mine rather than his.

What we see as problems are always relative to our wishes or expectations. To work on our dog’s problems is also, therefore, to work on ourselves. Are our wishes or expectations reasonable? If, on our walks, your dog wants to sniff every scent it encounters, ask yourself: “How much does he gain, and how much do I lose, if I indulge this behaviour?” There is an honest answer there somewhere, and it can form the basis of an accommodation, a pact, or contract of which compromise is a key ingredient.

I have lived with dogs almost my entire life, and my life has, accordingly, been a protracted process of problem solving. In service of this, I have devoured the literature on dog cognition – figuratively, that is (some of my dogs have been known to devour literature in the literal sense). Here are some of the more notable problems I have encountered. I don’t claim that my solutions will work for anyone else, merely that they worked for me.

The Aggressive Dog

Aggression is the most serious problem a dog can present. Usually, among dog trainers, discussion of this subject would quickly turn to training methods. These divide into two broad kinds: inducive and compulsive. Inducive methods reward a dog for good behaviour by way of a reward, typically food or praise. Compulsive methods use some degree of force: a lead correction or a verbal admonishment, for example. Each camp tends to regard the other as implacably evil.

I suspect that this debate is largely misguided. Training, of either sort, will never be the foundation of a relationship with one’s dog. I think that two factors modulate a dog’s behaviour with its human: inhibition and love.

My dog Shadow, an east German working line shepherd, is one of the most naturally aggressive dogs I have ever encountered. His predilection for aggression became apparent immediately, even though he was only a four-month-old pup. In a game of chase, my nine-year-old son fell over. When he tried to get up, Shadow pushed him down, and in every successive attempt his growling grew louder and his shoving more forceful. When I pulled Shadow away, he attempted to bite me.

My strategy was to get Shadow accustomed to, and more importantly enjoy, physical contact. I slept downstairs on the sofa with him for the first six months, something he grew to cherish. Whenever I said “Bedtime!”, he would jump onto the sofa and start kneading it like a cat. It was an L-shaped sofa, and we slept head-to-head. He grew to love this contact, which I think helped curb the more aggressive of his tendencies.

Exercises intended to develop his inhibition then built on this foundation. Inducive methods don’t work on high-aggression dogs. Mild forms of compulsion fare better. Shadow pulls. I stop. Shadow whirls around and snarls at me: “You’re pushing it, old man!” This is where all those nights spent on the sofa become evident. There’s enough love – or something close enough – to get the job done. De-escalation is key to these flashpoint situations. A weary “Oh, for God’s sake, Shadow. Don’t be ridiculous”, accompanied by a dismissive wave of the hand, is required. We walk on in silence.

The Anti-Social Dog

Does your dog hate other people coming to your (their) home? I would recommend identifying what it is your dog really likes; for many, this will be food. You can then arrange for your guest to supply it. This is something I have tried with Shadow. Shadow remains leashed while the visitor asks him if he would like some food and subsequently places the food on the floor in front of him. This is repeated several times, over several visits. This is a simple associationist training technique: Shadow comes to associate the visitor with good things that, in his mind, eventually makes them into a good visitor. The leash stays firmly on until the translation has time to take effect.

The Separation Anxiety Dog

Whether my wolfdog Brenin’s penchant for destruction was grounded in upset or boredom, I will never know. Whatever the cause, the result was the same: things, many and varied, were eaten. My first solution was straightforward, if unimaginative: don’t leave him on his own! At the time, I lived a life that afforded me this option, but I understand it is not possible for many, including myself, now. A canine friend might help but, and I can’t emphasise this enough, it is very important to put a dent in your dog’s behaviour before you introduce a new dog. Dogs learn behaviour from each other and the introduction of another dog may simply double the problem. First, work on the dog you have. Small increments are best. Start by shutting them away on their own for a minute. The next day, make it two minutes. Most importantly, before any isolation period, I would advise exhausting them. Now may be a good time to take up marathon running. A tired dog is not necessarily a happy dog but, usually, a less neurotic dog.

In a lifetime spent with dogs I have learned two lessons. First: things will get better. Probably. A young dog can have so much energy that it doesn’t know how to contain it all and the resulting bad (as we see it) behaviour will be an expression of this excess. My advice: be happy for them. The chances are that you were like this once. Second: stay calm. Dogs like calm because it helps them be calm. Conversely, fretting will make them fret. Dogs are very adept at drawing conclusions from our behaviour. If you react fearfully to a loud peal of thunder, the dog will conclude that thunder should be feared. Making a song and dance about leaving a dog on their own is a good way of convincing them that a terrible thing is happening. Ultimately, I think, the key to raising a well-adjusted dog is to create an environment that they can learn from. When my young sons fell over, their cries were met with hugs and warm words. These are precisely the things that Shadow came to value, and therefore these comforting actions conveyed something to him. This is what we value around here. If the cries of my sons were met with harsh words, or a clip around the ear, that would communicate a very different set of values.

The Happiness of Dogs: Why the Unexamined Life Is Most Worth Living by Mark Rowlands is published by Granta, £16.99

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.