Kendrick Redman came to the Pajaro Valley from Missouri in 1865, with his 9-year-old son James. They settled in Watsonville and farmed while living in a small house on Brennan Street, according to Aunt Vina Redman in the “Redman Family Papers.” The family moved in 1870 to a place along the Pajaro River, where Kendrick Redman raised potatoes and sugar beets. James Redman married Louise Werner in 1880, and she and 26-year-old James moved to today’s Redman Farm in 1882, which at the time was 120 acres. In 1887, Claus Spreckels built the largest beet sugar processing mill in North America on 25 Watsonville acres near Walker Street. The industry inspired the Redmans and other farmers to devote a total of 2,937 acres of farmland to sugar beets, producing 1,000 tons of beet sugar in 1892. In 20 years, James was raising 15 tons of potatoes and sugar beets per acre. (Prof. J.M. Guinn, 1903.)

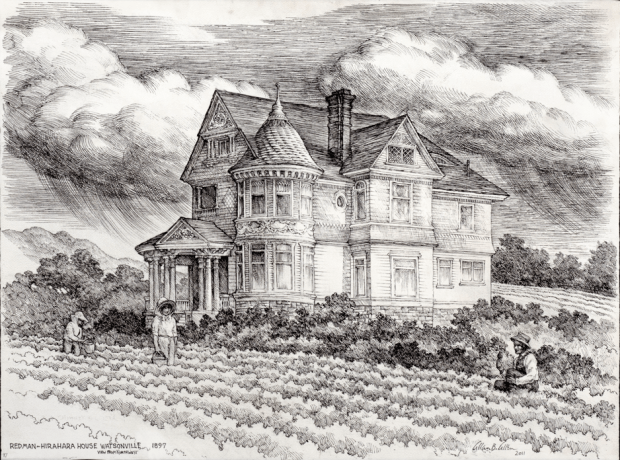

The Redmans loved their rural farm life yet craved the comforts of the city. They hired Watsonville architect William H. Weeks to design a Queen Anne home. Weeks was known for meeting middle-class budgets with style and function, charging $150 per room and upwards, to “give you the best work for the least money!” For a price of $5,000, they got a house with 14 rooms, five bedrooms, three covered porches and two balconies. Redman wanted his formal rooms at the front of the house, but from the back, it is believed the large room off the dining room was the mess hall for the farmworkers. The building was built with granite foundations, a first story of brownish-yellow beveled wood, a “Queen Anne shawl” of redwood colored second-story shingles, with white highlighting on trim, dentals, pillars and such. Ornamental gable moldings were a contrasting color.

By the turn of the century, Prof. J.M. Guinn wrote about the prominence of this farmhouse from the county road, as beautiful inside as it was out, with finishes of bird eye maple, oak and hard woods. The home was lit with acetylene gas, a home process which dissolved calcium carbide in water, producing a flammable gas. Since one pound of calcium carbide could produce about 4.5 cubic feet of acetylene, it was cheaper for lighting than oil, kerosene or “city gas.” It produced a brilliant white light, much brighter than other fuels.

Farming

Due to their expertise, Chinese Americans were the favorite field workers, until the hard times of the 1893 depression, bringing unemployed white workers, as well as new Japanese migrants, who’d work for less. Sandy Lydon’s book “The Japanese In the Monterey Bay Region” notes that by 1896 the economy strengthened, and a Watsonville paper observed there were 400 Japanese farmworkers in the valley, most in the sugar beet industry. Since James Redman had built his 1897 Redman House with two dining rooms, his mess hall may have served a crew of Japanese farmworkers.

Then in the years 1898-99, Spreckels hired Wm. Weeks to build a new sugar beet plant and company town near Salinas, to move the sugar beet industry out of the Pajaro Valley. Some made the extra effort to sell their beets over in Spreckels, but most farmers switched primarily to apple and strawberry production, turning Watsonville for a while into the Apple Capital of the World. Ed Reiter and Richard Driscoll introduced to Watsonville a variety of strawberries in 1904-05, which they named the “Banner Strawberry.” After World War I, local promotional brochures advertised the Pajaro Valley as the “largest berry field in the world.” (“Harvesting our Heritage”, 2017). When the Redman farm switched to strawberries is uncertain.

After James Redman’s death in 1937, the house and farm were sold at auction for $69,575 to J. Katsumi Tao, with Fumio Hirahara (a minor) residing there, who gained the title in 1940 for a $10 deed transfer. With the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Japanese Americans were relocated to internment camps in 1942, with the Hiraharas being moved to Arkansas. Yet they were fortunate in having appointed Watsonville attorney John L. McCarthy, to act as guardian for Fumio Hirahara, a minor and deed-holder. The agreement allowed McCarthy to borrow a sum of money not to exceed $50,000, to lease the land for crops, upkeep, and expenses.

Wartime

This sudden evacuation of skilled workers, many of whom were American citizens, was coupled with sending a generation of men off to war, leaving the farms understaffed, with many crops only partly harvested, wilting under nature’s own deadline. To save the industry, Washington, D.C., introduced the Bracero Program, importing Mexican field workers to replace the Japanese American workers. Even so, strawberry crop yields plummeted from 400 acres in production at the beginning of the war, to 40 acres at the end of the war. (Ibid.)

Meanwhile, some incarcerated Japanese Americans fought in the U.S. armed forces. Yet when the war was over, “Harvesting our Heritage” notes that returning to the Pajaro Valley was both hospitable and hostile. Some wanted Japanese Americans deported, while others said they are good Americans, unjustly treated. Because of the short time to sell their worldly goods before leaving, some were cheated, lowballed or lost everything. It took friends to act as caretakers just to keep their property. Those working for Driscoll or Reiter families found that their farms had been taken care of while they were gone and their client grower agreements reinstated. (Ibid.)

Yet the Hirahara family found locals wouldn’t sell them gas for their tractor or buy their produce, so they got their gas in Monterey and sold their crops to Los Angeles distributors. The Hiraharas housed four other displaced and destitute Japanese American families at the farm in a barn-dormitory, recalling internment camp life. Yet the Hiraharas achieved success through hard work and skill, selling their farm in 1982, with the matron Tayo Hirahara allowed to remain until her passing in 1986.

The farm was whittled down to 13 acres. The landmark was damaged in the 1989 earthquake, after which vandals looted some interior features. Later the porch columns were stolen but returned in a week by an alert antique dealer. The Redman Foundation was formed in 1998 to preserve the farmhouse and its open space as a gateway landmark, planned to serve as an agricultural interpretive center, winery and bed and breakfast. The National Register of Historic Places proclaimed the landmark property to be of national historic significance in 2003. The foundation sought restoration funding but went bankrupt in 2009. Watsonville-based Elite Agriculture purchased the property in 2015, to farm organic produce, and hopefully complete the restoration of this gateway landmark.

Demolition advocates

Instead, the Oct. 7, 2024, meeting of the Santa Cruz County Historic Resources Commission took the bold step to get the building delisted from the protections of the National Register, in order to demolish the landmark. Chairman Barry Pearlman said, “In our role as the HRC, we can’t ignore the Redman House, it comes up in every single session, it is the most significant obsolete historic property in the county.” He felt it necessary to get authorities to “initialize the process” to move the project toward demolition. Knowing how unpopular their approach is, one chuckled, saying they’ll have to be prepared to handle a lot of emails opposing demolition.

Pearlman felt Santa Cruz and Watsonville are going through massive redevelopment, “yet somehow we want to keep the image of this nasty old building intact.” He said, “The owners have that little shopping center, and they want to expand it, but right now, you don’t see it from the highway because it’s behind the Redman House. So (demolition) would be to their advantage, they’d have a better visual view of their hotel. … People can’t see there’s a Starbucks because it’s behind the Redman House. A lot of this is unspoken, because people don’t want to say unpopular things.”

Significance

The National Register of Historic Places documentation for the Redman-Hirahara House, and other studies related to the landmark, suggest its most important areas of significance are as follows.

1. It’s one of the most attractive farms in the Pajaro Valley, and a highly visible gateway landmark and iconic Watsonville farm house.

2. It is the work of William H. Weeks, who transformed Watsonville with about 150 structures, giving the town its distinctive character. He became the most prolific architect in California, designing buildings for over 161 California cities, plus others in Nevada and Oregon. This is thought to be his only farmhouse.

3. The landmark agricultural industries of Spreckels Sugar and Reiter-Driscoll Strawberries.

4. The affluence of California farming in an area of ideal growing conditions and many farmers as pillars of the community.

5. Japanese internment during World War II, and its aftereffects.

6. The migrant worker experience, some leading to farming success.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.