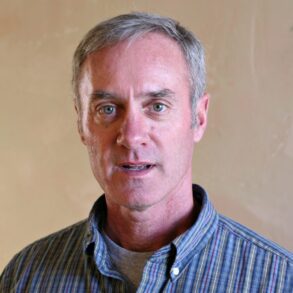

When Paul Buck drove past a skinny black dog on the side of the road during a visit to Tennessee in November, he wasn’t sure what to do.

When he circled back two hours later and she was still in the same spot, he figured he shouldn’t leave her there. A visit to a local animal shelter informed him it was unlikely the dog, now named Lady, would evade euthanasia if left in their or other shelters’ care.

“She was severely malnourished — she needed a home. She needed love and care,” Buck’s daughter, Kristen Adamiak, said Tuesday.

Buck ultimately decided brought Lady to his home on the South Side of Chicago, and the two have been inseparable ever since. Buck’s wife died in April 2022, and Lady keeps him company in her absence, Adamiak said.

“That’s totally his girl,” Adamiak said. “I was like, ‘oh my gosh, finally, something that makes him so happy.’”

So when Lady escaped Feb. 1, digging herself under Buck’s backyard fence, Adamiak was admittedly “freaking out.” With Buck searching the surrounding area, she called around to area municipalities and learned Lady was found by Oak Lawn police and brought to Animal Welfare League in Chicago Ridge.

What Adamiak didn’t expect was the saga that followed, including contested ownership, 16 days of asking to see Lady and, eventually, adoption to get her back.

While Lady was housed within the Animal Welfare League, Adamiak shared her situation with others on social media, leading her to discover multiple complaints about the shelter’s handling of lost pets.

Public perception

Chris Higens stepped into the role of interim president at the Animal Welfare League following protests alleging animal abuse and unsanitary conditions.

After a February 2018 Illinois Department of Professional and Financial Regulation investigation discovered improper euthanasia procedures and poor record keeping, Higens said she instituted a by-the-books protocol for euthanasia, purchased an expensive oxygen treatment unit and invested thousands of dollars into building repairs.

But Adamiak and other complainants say the troubles didn’t stop there.

Records obtained by the Daily Southtown found nine complaints filed with the Illinois Department of Agriculture between February 2020 and June 2024. In those cases, the state did not find any violations of the Illinois Animal Welfare Act that defines and sets rules for animal control facilities and shelters.

The Agriculture Department did not disclose complaints under investigation, but Adamiak and others expressed concerns the Animal Welfare League does not comply with the Animal Welfare Act’s regulations on how shelters accept and handle strays.

According to section 3.6 of the Animal Welfare Act, “when stray dogs and cats are accepted by an animal shelter and no owner can be identified, the shelter shall hold the animal for the period specified in local ordinance prior to adoption, transfer, or euthanasia.”

“The animal shelter shall allow access to the public to view the animals housed there,” the statute reads.

Lack of access

Lady went missing Feb. 1, with Oak Lawn police notifying Adamiak of her placement at Animal Welfare League that night. The shelter was closed the following day, so Buck went to pick Lady up Monday morning, within 10 minutes of them opening, Adamiak said.

Talking to the front desk worker, Buck was immediately told his dog wouldn’t be at Animal Welfare League, since he lives in Chicago.

“He’s pulling up his phone, like ‘see, this is the dog that’s missing. My daughter’s been posting all over the Internet,’” Adamiak recounted, saying Buck showed the workers photos of Lady.

The worker said the shelter required medical records to prove ownership of Lady, because she didn’t have a microchip. Adamiak said with Buck having owned Lady for several months at that point, he planned to take her to the vet but hadn’t done so by the time she escaped.

“They’re kind of giving him the runaround because he’s like ‘when can I come pick her up?’” Adamiak said. “They couldn’t give us a date.”

Adamiak said she and her dad visited the shelter multiple times that week, asking to see the dog in custody and confirm it was theirs.

It took 16 days of back and forth for Buck and Adamiak to see Lady again, with the Animal Welfare League ultimately requiring them to submit an adoption application for the dog based on a photo they posted of her online.

“He could have potentially been adopting a dog that wasn’t even her,” Adamiak said. The photo of Lady posted on the league’s website was blurry and the shelter had removed her distinctive collar, she said.

When Lady was brought out from her cage, Buck said he hardly recognized her. She appeared more like the scrawny puppy he picked up in Tennessee than the dog he had taken care of and grown to love, he said.

“I said, ‘that ain’t my dog,’” he said. “She was skinny as all hell.”

But when he and Adamiak looked closely at her chest, they saw the distinctive white spot that told them they had finally gotten Lady back.

“As soon as she saw us she was so excited, but then you could just tell she was like tired, like ‘get me home.’” Adamiak said.

Animal Welfare League responds

Adamiak chronicled her frustrations with Animal Welfare League on social media, where she heard the stories of others in the south suburbs who had been denied access to stray dogs there. They include Deb Deel and Connie Wilson who never found their dogs.

Animal Welfare League’s Higens has pushed back against claims they hide animals from the public and fail to comply with state law. The shelter posted on Facebook Feb. 28 that Adamiak was spreading misinformation about her experience and warned others to “not be fooled.”

Higens said Adamiak caused disruptions at the shelter, creating problems for workers as she and others tried to claim the same dog.

“Adamiak demanded the dog immediately. She screamed and made threats in AWL’s lobby, and the police had to be called,”the post read. “At first, Mr. Buck refused to submit an adoption application, but finally, a week later, he did so. After a vet exam, rabies shot, microchip, and the stray and medical hold, and after Lady had gained three pounds at AWL, she was adopted over to Mr. Buck.”

Higens said Thursday the shelter is compliant with state law in limiting access to strays to people who provide medical records, as photos of strays are available on its website.

Adamiak conceded she raised her voice and grew passionate trying to gain access to Lady, but left the shelter when asked to by police. She said she hopes her complaint to the Agriculture Department is taken seriously and that Animal Welfare League becomes more transparent and accountable to the public.

“I don’t want people to feel how I felt, how my dad felt,” Adamiak said. “I don’t want other people to have to deal with this.”

ostevens@chicagotribune.com

Originally Published:

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.