“Presbyterian discipleship occurs entirely from the neck up.”

I cannot recall where I first heard this critical joke, but it is one I repeat with great relish. It stands head and shoulders above other self-assured witticisms about Presbyterian intellectualism, which, let’s face it, get pretty tedious. More than being funnier than the alternatives, this quip also accounts for the very reasonable theological assertion that right thought will lead to right action. In a way, if you believe that orthodoxy (right judgment) will lead to orthopraxy (right action), then you have a solemn responsibility to do a lot of discipleship about what’s inside your own head. To be Presbyterian is in some sense to be an architect of grand mind palaces.

To scroll this publication, I suspect, is to be in rarefied intellectual air. Like me, you probably have a friend or two that you can text when you’ve read something striking or when you are untying an ethical knot. But like me, you probably also find yourself exhausted by the ongoing need to remain at attention. Attending to our constantly changing broader context, the world in which we praxy, is to shore up the mind palace and be held to high standards for the head inside which we doxy.

The world around us – our broader context – is sliding into an autocratic abyss, but more troublingly, our mechanisms for inviting others into our mind palaces and being held accountable for our patterns of thinking are breaking down, too. Our social networks are fraying, and our Social Networks tear down what’s left of those webs through poorly approximating and then monetizing our connections. It is in this morass that I turn with great relief to my dog, Melody, who – this is important – is dumb.

Melody’s dumbness belies a soaring capacity beyond any human I know, and that is worth taking seriously.

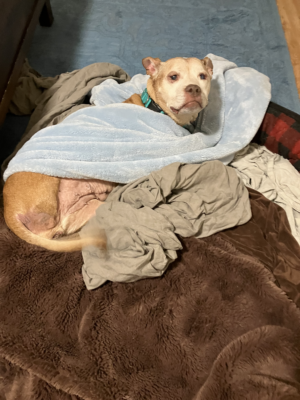

Melody is lots of things: three-legged, demented, deaf, and possessed of Cushing’s disease and megaesophagus (which is exactly what it sounds like, and which requires us to hold her upright for 10 minutes after every meal for the food to go down). But more than anything, she is dumb.

Melody does not sit, stay, play dead or roll over. She does not find value or purpose in interactive feeders. She is utterly untroubled by the backlog of unburned glucose in her brain pan. There are dogs that you can look in the eye and see that they are tracking, that they are looking for a job. In Melody’s eyes, one finds sweet and profound blankness.

Melody’s dumbness is an essential break from all the Presbyterian thought work. Clearly, she loves me just the way I am and much, but not enough – it could never be enough – ink has been spilled on this divine trait of our canine companions. But Melody’s dumbness belies a soaring capacity beyond any human I know, and that is worth taking seriously.

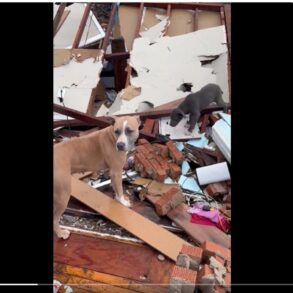

Several years ago, Radiolab did a series on intelligence. In one episode, the hosts discuss the idea that a serviceable measure of intelligence is the capacity to navigate problem space. I know of no living entity better able to navigate problem space than Melody. In November 2012, Melody was found wandering the streets of North Philadelphia with a mangled leg, likely having been hit by a car. Today, she commands the total obedience, love, and attention of her human subjects, not to mention all blankets. She has improved her circumstances exponentially and continues to do so with something like ravenous benignity.

Melody refuses misanthropy. She welcomes all humans she meets into her pack (dogs are another story). She declines to share my low Calvinist anthropology. For her, people are good. Even the vet’s office is a virtuous place with the people who fix her and into which she enters with cheeriness — such cheeriness, in fact, that on more than one occasion it has become impossible to replicate the issue for which we went to the vet in the first place.

But Melody’s anthropology also means that she is extremely demanding. She barks in the style of Tracy Jordan on “30 Rock,” shouting “Pants! Pants! Pants!” until his entourage burst in with a selection of trousers and a concerned, “You chafing again, Tray?”

Melody’s love for people is not in the vein of Mr. Rogers’ “Look for the helpers.” It is an ongoing certainty that the human world is entirely helpers.

Melody’s love for people is not in the vein of Mr. Rogers’ “Look for the helpers.” It is an ongoing certainty that the human world is entirely helpers. What could people possibly want, if not to help her in her time of need? And in wondering this, in that guileless, grace-filled, and good faith way of a dog, Melody finds a world full of people who do in fact want to help her in her increasingly common times of need. And the ones who don’t want to help or who are cruel, she seems just to forget.

I appreciate the Presbyterian desire for taut theories that guide good practice. I also appreciate the self-care discourse and the understandable desire to pull back from … all of this. Simple calls to do the right thing may give us warm and fuzzies about our own individual piety but they remain as effective, in a broader sense, as “just say no to drugs.” I’m not sure any of it is really working out.

I know of no living entity better able to navigate problem space than Melody.

So, I’m considering Melody’s way. I’m considering believing in people, letting go of taxonomies of helpers and hurters. Rather, Melody’s example challenges me to expand my self-interest to include an ever-growing pack such that all are enfranchised into my self-interest and grafted into my community where everyone is a helper.

A good faith and grace-filled engagement with the world; A theology of the pack: At its core, Melody’s way is setting aside being smart or correct or pure and instead guilelessly assuming that these are all our problems and that we must engage the question, “What will help us navigate this problem space?”

As I finish writing these last words, Melody has begun panting from under her pile of blankets. She is hot and thirsty. The barking will start soon. She will ask for help — and I will give it because her problem is my problem. She is right to assert that in problem space, we need each other, we implicate each other, and we are connected. This is worth a try.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.