“Will she ever wake up?” That was the question all my loved ones were asking themselves—doctors had no answer. There was no way of knowing.

The losses throughout my college experience started with my childhood dog, Duke, dying early into my freshman year. In my sophomore year, my mom got sick with pancreatic cancer—my uncle was paralyzed in a swimming accident—and just months after my mother’s diagnosis, she died. She left me her little dog, Teddy, who became my constant companion.

A few years passed, and I was finally in a solidly stable and good place. I walked in my college graduation ceremony with just two classes to go. I was soon to be a college grad with a promising future. Then, the accident happened just weeks into my super senior semester at Humboldt State.

Teddy and I were taking a walk before dinner, when we were hit by an intoxicated driver, on September 7, 2019.

I wonder why that day, I happened to take the same road at the same time as the driver that hit us. She smashed into us—going between 25 and 30 miles per hour—as we crossed the crosswalk. Her car was probably barely dented, but for us, it changed everything.

Teddy died instantly on contact, and I hit the ground so hard my brain was shaken inside my skull. I suffered diffuse axonal injuries to my brain. DAI is a type of traumatic brain injury. Axons all over my brain were torn or sheared—like shaken baby syndrome. The accident left me with physical, emotional, and cognitive deficits that I will have to deal with for the rest of my life.

I don’t remember being treated while still in Northern California. I’ve seen pictures of myself being flown to my hometown of Los Angeles where I could be in hospitals close to and surrounded by my support system—although being back home was the last place I wanted to be after college.

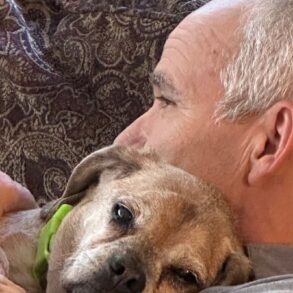

Emily Owen pictured with her dog, Teddy, before the tragic incident involving an intoxicated driver (left). Emily pictured in a helicopter after being struck by the driver while walking her dog (right).

Emily Owen

When my eyes then opened for the first time in weeks, they were unseeing. Nothing would register for weeks. When I became responsive, I could only nod and point. I was partially paralyzed on my right side. I had to relearn everything like a young child—even though I’d just graduated college in the months leading up to our accident.

My family, friends, and all my loved ones rallied around me, waiting helplessly to see if I’d even wake up during the first weeks. No one knew when—or even if— I’d open my eyes, what my physical deficits would be, or how my cognitive abilities would be affected, how I’d heal and to what extent.

I began my seemingly endless healing journey when I became conscious, aware of what was happening, and could respond to the world around me. I love to sleep, so now I joke about how I love to sleep so much that I once slept for more than two weeks!

In a single moment, the driver who hit me irreparably changed my life. It probably changed her life, too. However, she went on living her life without any permanent damage. I, however, spent weeks in a minimally conscious state—months in various hospitals and facilities—and attended intensive daily neurorehabilitation for almost two years after I was discharged from the hospital in December 2021.

I spent those years doing countless hours of physical, occupational, cognitive, and educational therapy. The emotional toll the accident took on me and everyone who loves me is difficult to describe.

I realized early on that I had a story inside me—just bursting and begging to get out of my head. I needed to write it down to help me process what happened to me.

I started writing about what had happened to me just a month after I got home from the hospitals. At first, I had no specific intentions—I couldn’t even type. So, I dictated the beginning to my aunt. She would even have to give me cues and ask me questions so I could continue. “How did that make you feel?” “What were you thinking after that happened?”

Once I had the strength and the dexterity to type, I would write daily at the end of the day. A mason jar full of coffee sat between me and the computer. Tap. Tap. Tap. Just with my index fingers at first. For hours. It began as a way for me to tell my story, and then it took shape and became chronological. My aunt helped me organize it into chapters. It started to look and feel like a book.

The process was so cathartic that I couldn’t stop. It began with me just needing to get my story out of my head. Then, it became a vehicle to help others going through the same journey. So, my book was born. I named it The Best of the Worst: My TRUE Story of Surviving and Thriving After a Traumatic Brain Injury. I recently released the book under the name Emily Silver Owen—adding “Silver”, my late mom’s maiden name, as my middle name to pay tribute to the woman who brought me into this world.

My book became a way to wholly accept, understand, and rationalize the many years I’ve spent recovering. The day I was injured, a version of me died along with Teddy. Five years later, I’ve grown into referring to that day as my re-birthday. It’s become a day that serves as a reminder of how fragile this life truly is and how everything can change instantaneously. You never know how long a good situation will stay good.

In addition to causing a slew of physical and emotional challenges I will always be working through, my brain injury made me neurodivergent. Neurodivergence just means that someone’s brain works differently from most people’s brains— whether due to autism, ADHD, or a brain injury like mine.

Just because someone looks a certain way doesn’t mean much. Traumatic brain injuries are called invisible injuries. I have learned that just because you can’t see it, doesn’t mean it’s not there. Some of us need extra explanations, slower explanations, more time to process what is asked, and even extra instruction. Reminders are helpful and important—and are just the thing to ensure something gets done.

We need those around us to try to understand us and sometimes offer a helping hand. We may not need much, but support helps. Becoming and accepting my neurodivergence changed my life forever. I can never go back to the neurotypical life I led for the first 22 years of my life. The word neurodivergent isn’t even in my book because it’s an identity I’ve grown into. It’s an identity that feels comfortable and fitting.

Now, in 2024, I’ve enthusiastically claimed my new self—Emily 2.0—as neurodivergent. I have stepped into my new identity. Although the process of writing my book is now a blur, it has had lasting effects on me. It helped me accept and understand the changes in my brain.

Accepting my neurodivergence has helped me get to where I am now. Becoming, accepting, and embracing my neurodiversity has taken some of the weight off my shoulders. It allows me breathing room to make and learn from my mistakes without always getting frustrated with myself for not getting something done as fast as I might have been able to in the past.

I am committed to raising awareness about traumatic brain injuries and have a few works in progress. I am looking forward to sharing my stories—either real or imagined—with anyone who wants to read them!

Emily Owen is a writer, and author of “The Best of the Worst: My TRUE Story of Surviving and Thriving After a Traumatic Brain Injury“.

All views expressed are the author’s own.

Do you have a unique experience or personal story to share? See our Reader Submissions Guide and then email the My Turn team at myturn@newsweek.com.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.