Historian Jeff Murray takes a look into West Hartford’s past to uncover some surprising information, stir up some memories, or reflect on how much life has changed – or hasn’t changed at all. Enjoy this week’s ‘From West Hartford’s Archives’ …

By Jeff Murray

This photograph of a West Hartford resident’s beloved dog is a simple snapshot. They were often more than just pets though. They were guardians, workers, companions, and known to everyone. There are dozens of stories of faithful hunting dogs, roaming strays, and pampered pups.

More than a hundred years ago, dogs in this town were often the watchers and protectors of the home and land, more than today. In an era before technology and even organized police, many families kept dogs as watchdogs to deter trespassers or alert their owners of any strangers approaching the farmhouse. Hunting was a common pastime and dogs assisted with hunting small game, like rabbits and birds.

The dog in the featured photo appears to be a mixed breed with a terrier-like appearance. Terriers, spaniels, and retrievers were popular breeds in the 1890s to the 1920s. Farmers would often use their dogs to help with herding livestock or protect the poultry against predators. Terriers were often bred for their hunting instincts and were considered highly effective at removing pests, like rats and mice. Outside of the standard hunting, they would even hunt on their own, even to the dismay of neighbors. A prominent farmer had several of their valuable sheep killed in his pasture by a few Great Danes kept in the area. Sometimes, dogs went missing while hunting or recovered from traps set for other animals. Charles Flagg’s St. Bernard was found stuck in a fox trap in the woods near his house and had to be nursed back to full health.

Beyond hunting on the farm, specific breeds were useful in other industries. The market gardener Paul Thomson, who came over from Scotland in the 1870s and built a large estate at nearly all four corners of Park Road and South Quaker Lane, had a Newfoundland dog. One of Thomson’s first jobs here was cutting ice on the pond a mile and a half from his house, and his dog was known to stay out on the ice to watch for the workers in the morning. Newfoundlands were known for their strong swimming ability, bred as a working dog for many fishermen in Newfoundland, Canada (many of these fishermen were Scottish immigrants, like Thomson). In the 1880s, a single dog was considered the “best preventative measure” against the “nuisance” of Italian immigrants who came to West Hartford to search through the trash for old clothes, fabric scraps, and textiles.

Sometimes, man’s best friend was also the cause of greater terror in the neighborhood. In the 1880s and 1890s, “mad dog” scares were frequent. As West Hartford grew and expanded in the late 19th century, there was an increase in the number of stray and roaming dogs. With little regulation or understanding of disease containment, the practice of letting dogs roam freely brought the risk of rabies spreading. Outbreaks of rabies would cause widespread panic. Rabies was also a death sentence once symptoms appeared. One of the most notable scares was in the summer of 1891 when Seymour Steele’s bulldog became infected with rabies in the Center and went on a rampage throughout the town for nearly a month, laying low in the woods in the north end. From bites, caution, and in some cases paranoia, eight more family dogs and two cows were lost to the scare that summer. Everyone knew everyone else’s dog, so if a strange dog appeared on the streets, it caused quite a stir.

The local press loved dog stories, good and bad. In June 1898, a Hartford saloonkeeper was accused of enticing a dog away from David Moseley’s house on North Main Street. The saloonkeeper in question wrote into the Hartford Courant and sternly corrected them that he did no such thing and that he was just enjoying a chance encounter with the pup on his way up the road.

Even things we might take for granted today were published. In 1903, Charles Fulton saw a deer on North Main Street. His dog barked at the deer and it ran into the woods. That was the story published in the newspaper for all to read!

Other stories were simply odd. In 1907, Constable Strong inspected the woods behind the Sears home at the corner of New Britain Avenue and Newington Road after he heard complaints that a “gypsy camp” was staging there. The term “gypsy” was generally associated with the nomadic or homeless population, not necessarily of the fortune-telling caravan stereotype. In many cases, New Britain Avenue in Elmwood was a popular conduit, just off the road from Hartford. There were homeless camps on the railroad bridge for several months nearby in years past, so it made sense that they would be in Sears’ woods next door. When Constable Strong showed up though, he instead found a local dog trainer and his wife conducting a wagon training eight dogs to “star” in the theaters in the upcoming winter.

In the early 1900s, the West Hartford constables began earnestly enforcing the law that required licensing dogs. In 1902, there were hundreds of dogs in town, but only 145 had been registered. Constable Strong prowled around town looking for any unlicensed dogs, with some arrests. He would later be made dog warden.

After Alfred Johnson of Raymond Road was found to be keeping an expensive female dog without a license, he insisted he would rather kill the dog than license her. I would rather believe the dog escaped and found a loving home with someone who considered her worth the cost of a license.

The town also pushed for the muzzling of dogs off of their owners premises after they received several complaints. When the order went into place in 1907, the number of dogs roaming the streets noticeably declined, although the selectmen would later walk back the order after some pushback. With the expansion of the number of schools across West Hartford in the 1920s, town officials enforced a strict “no dogs around schools” policy after a number of children were knocked down by the hordes.

Dogs were also a symbol of status, especially purebreds. The Victorian era had popularized them as fashionable pets, with dog breeding becoming increasingly popular during this era. The American Kennel Club was founded in the 1880s and helped establish breed standards. Many middle-class families, including those from West Hartford, took pride in showing off their dogs. In the 1910s, town residents entered their pets into a local dog show held at the Rosemary Farm at Bishop’s Corner for the benefit of the Girl Scouts. Rose Cohen of Kingswood Road entered her Scotch Collie puppy “Budd XI” in the 1922 show. George Kolb of Albany Avenue even participated in the Westminster Kennel Club’s Dog Show at Madison Square Garden in 1923 as a judge. Newspapers shared photos of local pets and snippets of their family stories from all across West Hartford in the mid-1920s.

Above all though, dogs, like today, were simply loved family members. Clarence Hubbard’s dog “Hub” had a funeral in a nearby stable in 1893, attended by all the neighbors. John Browne’s prized dog “Bobbie” spent a considerable amount of time on his farm on Farmington Avenue. Undeveloped woods were a prime location for deer, apparently followed by “all the pet dogs” of the region. Colonel Louis F. Heublein had “Duke”; William Hickmott Jr. had a Belgian Sheepdog named “Loki”; and families consistently took in orphaned dogs.

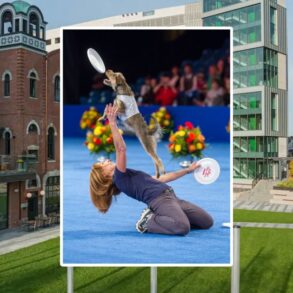

Dog-drawn carriage on the White farm at the corner of Outlook Avenue (c. 1895). Photo courtesy of Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society

Children grew up with them as wonderful working companions. They were often used to pull small carts, particularly with children. They were a practical way for children to transport small items and they also served as amusement and a display of affection. In the second photograph, a small Boston Terrier or Bulldog mix is seen “dog carting” on the White family farm off Outlook Avenue in the 1890s.

In 1922, someone wrote into the Courant to suggest that Walbridge Road be renamed “Dogville.” He was livid that dogs were allowed to run loose on that street all the way through to Fern Street. Citing the Prohibition era, he said, “Take away a man’s liberty, throw him into jail if he is detected having a glass of wholesome beer or wine, but for the Lord’s sake, don’t go back to the old Roman days and feed him to the dogs.” He said there were countless numbers of German police dogs, bulldogs, collies, and mongrels “making up the most treacherous and vicious bunch of animals imaginable,” consistently attacking the mailman working on Walbridge Road.

Dogs in West Hartford were loving family members, devoted working partners, and bloodthirsty hounds, depending on who you asked and when. Some things never change.

Like many dogs of the past, Millie, seen here perched on her favorite ottoman, is this editor’s loving family member. Photo credit: Ronni Newton

Jeff Murray was born and raised in West Hartford and has been involved with the Noah Webster House & West Hartford Historical Society since 2011 when he was a high school student and won the Meyer Prize for his essay on local history. Jeff routinely volunteers as local history researcher uncovering information for numerous museum programs such as the West Hartford House Tour and West Hartford Hauntings. Jeff works as a data analyst at Pratt & Whitney.

Like what you see here? Click here to subscribe to We-Ha’s newsletter so you’ll always be in the know about what’s happening in West Hartford! Click the blue button below to become a supporter of We-Ha.com and our efforts to continue producing quality journalism.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.