War Dogs

The Airport Animal Center

The facility lies two miles away from the main terminals but within the grounds of the airport, at the end of a service road that skirts a pond where geese flock during their migrations. It’s in the shape of an enormous U, and equipped with stalls, bathing areas, runs, a paddock out back, and rooms that are advertised online as suites.

Currently being boarded are: five dogs and two cats in quarantine before they move on to their final destination; three horses, including a polo pony who has finished a competition in England and will eventually head to his home, in Maryland; and ten birds in cages who by the end of the week will relocate to a renovated room that, at a certain hour of the morning, when the sun hits a wall newly papered in forest prints, has the serenity of a spa.

The day so far—an afternoon in early June—has been a quiet one. There are fifteen employees on shift, including a team of veterinarians, janitors, trainers, a driver who has gone to meet an airplane from Germany that is on approach, and two childhood friends, named Brian (twenty-two, living with his mother) and Tess (twenty, on summer break from college and staying with her parents), who are sitting together on the steps inside the delivery entrance.

Brian, who works with the dogs, is rubbing the side of his face and waiting for the driver. Tess, who works with the horses, will be two minutes late for her shift at the stables and is trying not to think about cigarettes. They’re in the middle of a discussion about whether a “war dog” is, by definition, a dog who works for the military, or if the term can be used for any dog who is in a war. They’d look it up, but the Wi-Fi is spotty out here.

Today, Brian has been assigned to one of two dogs coming in from a military base outside Berlin. He knows they’re originally from Afghanistan and that the one he isn’t responsible for is severely dehydrated. He pins his tablet between his sneakers and keeps checking his phone for service.

What Tess really wants to talk about is Brian’s mother, who flew out on an airplane last night and is about to land, half a world away, in Seoul, but Brian wants to talk only about the incoming dogs, not his mother or his father, who has just died and whom he has no memory of whatsoever.

It annoys Tess, the way he pretends not to care. She wants him to be better than that. She wants him to be better; suddenly, all this week, every little thing he does doesn’t seem good enough. Like the sandwich he made for her, an egg salad on rye with a hearty dose of paprika and parsley flakes, wrapped in tinfoil, which she holds in her hand right now as if it were a bomb.

What Brian doesn’t know, because Tess hasn’t told him, is that she can no longer eat what has been her favorite sandwich for all the years they’ve known each other, because if she opens up the tinfoil and smells the egg salad she will retch right then and there, the way she did this morning while making coffee for her dad, who, thank God, was in another room, obliviously staring at his e-mails.

Brian holds up his phone; it’s finally found some service. He searches for “war dog” and scrolls down, but all he sees is site after site about a movie they’ve never heard of. There’s no answer to their question.

Honestly, Tess says, switching to Korean and standing up. Who gives a shit. They’re just dogs.

What’s with you? he almost says, but then he knows that it’s him: he doesn’t feel like talking about his father. Or his mother up there in the air, almost to South Korea. Or the fact that she’ll be picked up by his father’s other family, which is how he thinks of them, and taken to his father’s house, where there’s supposedly a taped-up box that he left for her.

It’s probably some old jewelry she left behind. He returns to his phone, pretending to ignore Tess walking away, her gait different this past week, more careful, more considered—maybe that’s how they walk in college, he thinks—as a plane nearby touches down.

War Dogs

They’ve been in the air for seven hours, though that’s only today. The dogs have been travelling for days.

They’re brother and sister, and they’re both mixed breeds, maybe some shepherd in there, or something more compact, like a Malinois, with a little bit of the laziness of a Labrador and the light-footedness of a Jindo. They’re five years old, fifty pounds—give or take a few—each with pointy ears and the sister with a pale streak of fur across her chest.

They’re in crates with no view out the sides, only the front and the back, though the brother has taken comfort in knowing that his sister is in a crate beside him—he can hear her breathing. Even in her fatigue and sickness, she is breathing, and he focusses on that while the belly of whatever they’re in shakes as though the whole world is shaking and screams more awful than an animal screaming and whirs and then a light comes on and suddenly a door is being lowered and men appear, silhouetted.

He squints in the sunlight. There’s a blast of air as his crate is lifted, his sister’s crate is lifted, and they’re both carried outside to a truck, where, briefly, as he senses the motion of a man’s arm and hears the hum of electricity and smells sweat, fuel, concrete, soil, and a bird carcass near water, the crate he’s in swings high up—like that child he once saw on a swing set on the television—and he catches the blue of the sky that is not the blue of the sky he knows.

The Escalator

Roughly sixty-nine hundred miles west of the airport and thirty-six thousand feet above sea level, the flight to Seoul is about to begin its descent. Near the back sits Brian’s mother, who has been woken by her row neighbor, a boy who is climbing over her to use the bathroom before the seat-belt light comes on. He says sorry, in Korean, and keeps going, hopping over her in his sweats in a way that causes Mary—she has gone by Mary for so long in New York that it is her only name—to miss being young.

She drifted off because she hasn’t been sleeping. She hasn’t been sleeping because in her sleep she’s been having the same dream about him, her late ex-husband, almost every night since she heard. In the dream, after he collapses in the way she imagines he must have collapsed, he gets up, and continues riding the escalator in the shopping mall where he was a security guard. In the dream, Mary waits for him at the top, barefoot, in a new dress she’s bought, and when he eventually appears she asks flirtatiously if he can help her with the zipper.

It’s a ridiculous dream, but she keeps dreaming it, every time she shuts her eyes, and, when she opens them, she thinks about what really happened, which is that he collapsed right there on the mall escalator, heading to a higher floor. He collapsed and slid down a little on the steps. She thinks about how no one helped him right away, only moved aside, afraid that he was sick and contagious, until his shirt got caught at the top and his neck almost broke.

She had not seen him in almost two decades, since she immigrated to New York, taking young Brian with her. She hadn’t even known until recently what he did for work, what his days were like, where he lived, whether in a city or on the outskirts of one or deep in the countryside. She knew that he had remarried, and he and his wife had a daughter. Mary hadn’t even been sure if the girl knew of Mary’s existence.

But then, just over a month ago, the girl called the apartment in Jackson Heights where Mary has been living ever since she arrived in New York. She was surprised at the ease with which they slipped into conversation. The girl’s voice was steady, patient. She said someone at the local church had known Mary’s parents and knew where she lived. She said that her dad had sometimes spoken about Mary, and, when Mary asked about what, the girl didn’t respond. She then told Mary about the box they had found, in a drawer in the nightstand, a small box, one of those that could hold a mug, but they didn’t think it was a mug; it was taped up, and had Mary’s Korean name on it, and they hadn’t opened it.

The girl asked what they should do with it, whether they could send it to her, and Mary hesitated. And they stayed that way for a while, not uncomfortably, each of them silent and holding a phone, at opposite ends of the world. The girl was calling from outside because she could no longer stand being inside, and Mary sat beside the half-moon-shaped table in her kitchenette, the wall covered with old crayon drawings, while water boiled in a pot.

It was at the same table, a week later, that Mary told Brian about her decision to go. Brian had just come home from eight hours at the airport. Mary had watched Tess drop him off, wondering if she was going to come up. It wasn’t even a trip Mary could afford, but she was going to ask the Korean BBQ restaurant where she worked if she could take on a few extra shifts and then go. She was going to meet her ex-husband’s family, and she was going to pick up the box with her name on it, and maybe visit her old neighborhood for a night.

That’s fucked up, was Brian’s response as he sat down, and before Mary understood what was happening in her body she had leaned over and slapped him, hand flat and tight.

She held her breath. She had never done that before. Her hand began to shake as her mind wandered: whether her son would remember this moment forever; what her ex-husband’s favorite store was at that shopping mall; whether there was a girl behind a counter he had a crush on; what could possibly be in that box; and whether he had still been alive for a few seconds after he collapsed and whether he had felt it when he got caught in the escalator.

Yeah, Mary said, and lit a cigarette. It’s all fucked up. Yeah.

Brian rubbed his face. And then, to her surprise, he burst out laughing, because he always thought it was funny when his mom cursed in English.

In the Forest

He’s an Argentine polo pony, a bay, fifteen hands tall, all muscle, with a sleek coat. He doesn’t mind the heat, can compete longer than most horses, and has a temper that can flare on occasion if a stranger is handling him. He’s been here a dozen times, enough for the place to stay in his mind, the way the dirt from the grounds he played on is still on one hoof, so that when he leans down to smell he can picture the far hills of wherever he had been.

Ramsey—the polo pony—is in the middle stall of the Airport Animal Center stable, on the left side of the U-shaped facility. He is waiting for hay to be brought and his water to be refilled when he understands that something has happened to his vision but he is unsure what, exactly, this might be. It is like a narrowing. Like the stall walls have thickened and the ceiling has lowered and the light has dimmed. He wonders at first if there’s a fly mask on him that he’s forgotten about, but, as he shakes his head, he knows his face is uncovered. He tries to remember if something or someone hit him in the head during a game.

He longs to be outside. He pictures the fields he’s played on. When he pictures something in his mind, it is whole, and so he stays in it—a field, a ball, the control and the chaos of the sport. How, once, he almost stumbled in the middle of a game, smelling, inexplicably, on the wind, his mother’s belly.

He hears footsteps; they belong to the young woman named Tess. She’s carrying the hay in a wheelbarrow, filling the buckets hanging on their doors. He can see her only when she is very close, and in his frustration he calls to her, not realizing that she is already there, reaching out to calm him.

Tess is certain that he is hungry and bored, this horse who has passed through here so many times she wonders whether he has grown tired of the travel. She does not expect him to be so startled when she touches the space between his eyes, but he jerks away, and she looks down, wondering if something is in her palm.

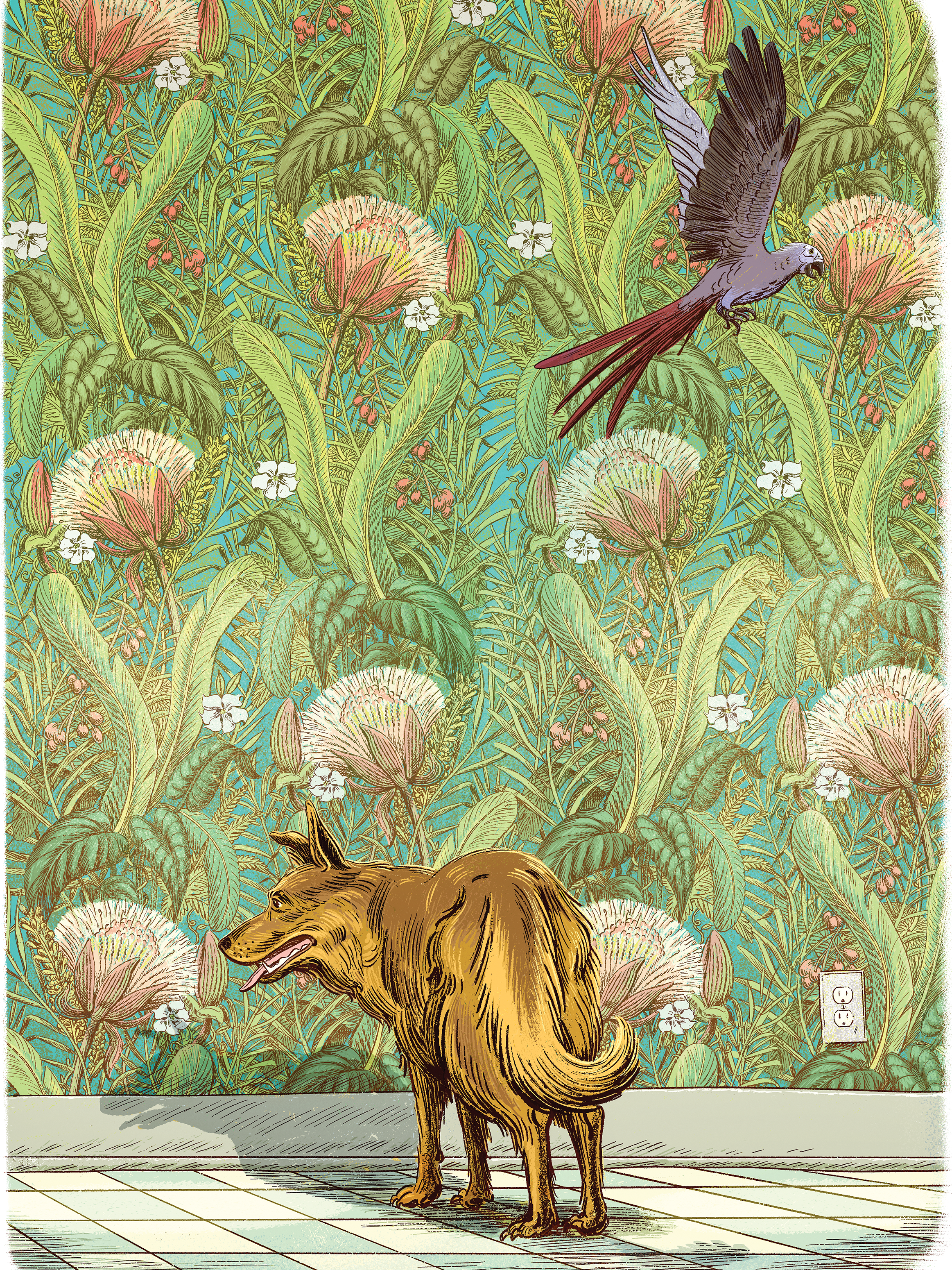

Ramsey, you brat, she says, and blows him a kiss, and heads out, intending to fetch more water for the three horses. Instead, Tess finds herself in the room that has just been wallpapered, the one that will soon be the new bird room, though no one is working there today. She has begun to go there when no one is around, to sit on a stool in the middle of the room and stare at the trees on the walls. Stare so long it is like she is walking into the forest, a thought that calms her, the trees and the sunlight on the trees.

It’s like there are no airplanes passing overhead.

She shouldn’t have snapped at Brian. Or said what she said about the dogs. Or thrown away, untouched, the sandwich he’d made for her. She shouldn’t have done this and that. She misses the two of them from a week ago, before she discovered why she was throwing up. A stark line has formed between the before and the now, and she doesn’t know what to do about it. Why is it that she thinks of him differently now? A little less of him? That’s unfair. The way she’s certain her father thinks less of him now than he used to because Brian doesn’t want to go to college.

When she is absolutely still in this room, she is free. Free to walk through the forest and think and come to a decision, because suddenly she needs to make decisions. When she is at school in the upstate town, there are moments when all she does is think of the animals here, and of her father, of taking care of these animals on their way to somewhere else, and how one day she will build a place for animals who never have to go somewhere else. And she remembers Brian, that one gentle constant in her life, the two of them meeting on the sidewalk lifetimes ago because they lived in the same neighborhood, where her father and his mother went on one date, and never again.

She smiles for the first time today. She tries to see herself as much older. And then she tries to see who is beside this older self. If she keeps walking in the forest, she believes she will see and enter a future that is clear and welcoming, where there is a fullness and clarity to the days, the way there used to be. But maybe that is what it means to get a little older. To feel less full and clear. Could that be? What did her mother feel when she saw her for the first time? Twice this week, in the afternoon, Tess has called the local library where her mother works, wanting to hear her voice, only to hang up.

She keeps walking in the forest, crossing from one path to the next, ignoring the planes passing over the canopy, until she hears the distant whinnying of Ramsey and remembers the water.

Slip Lead

He doesn’t even know the dog’s name. No tags, nothing in the manifest the driver passed to him. “TBD,” it says, in the section where there is normally an anticipated checkout date.

They are in an exam room together where the dog he’s been assigned to, the healthy one, has been cleared, and Brian is supposed to take him to his suite. Brian puts a slip lead on over the dog’s head, but the dog freezes, then pulls hard, forward, as if he wants to pull a sled. Brian takes the lead off. He tries to feed the dog a treat, but the dog sniffs and looks away. He’s probably wondering where his sister is.

Brian says, She’s in good hands. She’s with Tess’s father. Tess is my . . . he pauses. He wants to say, Love of my life, in the most sincere way possible, but it gets caught down in his throat. The dog looks back up at him. Brian thinks there’s a little Jindo in him, and that pleases him. He says a few words in Korean, and the dog considers him.

Brian checks his phone, thinks he heard a ping a moment ago, thinks maybe his mother has landed, but there’s nothing, no notification of any kind. He points the phone at the dog, wanting to snap a photo, to text Tess and ask what to do about the lead, but the dog’s ears pin back.

Fair enough, Brian says. He cracks open the exam-room door and peers down the hall. It’s a quiet day. The faint whir of a vacuum comes from somewhere nearby. He says, Shit, come on, and the dog follows him out, unleashed, the two of them hurrying to the suite, where the dog sits on the dog bed and Brian, thief-like, sits cross-legged on the matted floor next to it. The dog pants. Brian slowly raises an arm and pets him. The dog lets him.

This works, Brian says, and leans back against the wall, the dog panting less, the faint whinny of a horse, an airplane.

He strokes the dog between his ears and down his back. Roger, he says, quietly, almost to himself. You look like a Roger. That’s Tess’s dad. Or a Charles. Or Egg Salad. How about Egg Salad? Egg Salad, where are you coming from? Are you going farther after this, or is someone coming to pick you up? You still have a dad?

He looks up from this vantage point at the slip lead hanging on the hook, glowing a little in the hallway light. These past few weeks, a thousand times a day, it seems, he has been trying to remember something about his father, but nothing comes to him. He doesn’t even remember the trip and immigrating here or the first years. Only some faint memory of the glide of a stroller and the colorful hues of storefront signs at night.

Because he was a horrible drunk, Brian’s mom used to say, when Brian asked why they’d left, but for some reason he was never angry about any of it—his father and their leaving. Maybe he will be in some future time. But he doesn’t know what he feels now. He feels nothing but how he feels about Tess, truth be told, but Tess is in school upstate, and so they only really see each other in the summers, and who knows where she’ll go after school. She’ll start a farm in some town like Chatham and care for retired horses and have a million dogs. Dogs like this one over here whose history he still doesn’t know.

He scratches the dog’s chest and imagines Tess in overalls with sweat on her brow, and then he thinks of the night he told her the news about his dad, a little over a month ago. She had just come back from college. They were sitting on the hood of Tess’s car on the side of the road where they sometimes parked, facing the fence line of the facility and sharing a cigarette before she drove him home.

They said nothing else to each other, each of them thinking of death and what happens after death. And then they had another cigarette. The facility’s lights were dim, and night caught in the pond water. And then she took him to the back of the car, and they made love the way they sometimes did, for years now, not knowing what exactly it was between the two of them, what to call it, just that it was; it was a kind of history, the two of them, and had always been.

The Photograph

The sister is hooked up on an I.V. and resting while Tess’s father, Roger, a vet, sits in a corner, his laptop open beside a microscope. He’s gone over an aspirated sample of a bump he wanted to check on the dog’s front leg—it was nothing. He swivels in his chair and reads again the little information he has on the two dogs: They understand English commands. They have an owner, a translator who worked for the Americans in Afghanistan. He doesn’t know who, but someone was able to make arrangements for all three of them to get out. The owner was supposed to have come today, too, but there’s been no word—he must’ve been delayed—and Roger is waiting to hear when the man will arrive.

They’re miracle dogs, Roger thinks. It’s been in the news, the troops pulling out and so many others who had been helping for decades being left behind. He wonders what goes through people’s minds when they make decisions like that, and then he wonders about the person who was able to save two dogs.

And what awaits them now? She’ll recover, this one, and they’ll live long lives. Maybe they’ll be happy in the countryside hunting squirrels. Or maybe they’ll be taken to a big American city. Which was what he had wanted when he came here forty years ago, leaving his father behind in the misery the man mired himself in, to start over again. He wanted quality shoes with sturdy soles and a big car. To walk through the advertisements in Life magazine: smoke cigarettes on a sidewalk under a skyscraper in Manhattan, eat cake, sail on the river, be with women who wore stockings.

Except for the occasional slice of cake, he does none of those things. Cake for his wife’s birthday, or for Tess’s, or when Tess comes back home on breaks during college. This child who used to run to him if she fell is suddenly a woman who wants a farm with animals. He wonders if it’s because of what he does for a living or if it’s for reasons unknown to him—he’s never asked.

He made a promise to himself to love whatever she loves. His own father wanted him to be a doctor and then spent the rest of his life making fun of his son to his war-veteran friends, laughing about how he became an animal doctor instead.

Who cares about the animals? his father liked to say. A bomb is falling every day. You have a child on one side and a pig on the other. What do you do?

Nothing, Roger once said back. We huddle and we pray, and we all die.

Is it the memories of his father that are bothering Roger today?

He knows something is bothering Tess. It’s in the way she keeps going still, not here but at home, as if she wants to step outside time for a little while. Usually, in the summers, she can’t stop doing something. He’s been wondering if there was an incident at school.

Or maybe it’s Brian. He wishes they’d met when they were older—Brian adores her; they could marry. He’d even look past the fact that Brian seems to have no interest in college or that his mother is nuts. This woman who, on their first meeting, slid across the booth, pressed her lips against his, then burst out crying in the middle of the restaurant, all their neighbors looking.

How old were they then? Lifetimes ago. The truth was that the woman he would go on to marry, Tess’s mother, had set them up. She was working at a Korean community center that Roger visited some nights to have a meal, and she would tease him about how he was getting old and getting old alone was no fun. Mary had just arrived in New York, with a young child, and knew no one. All of them were in Jackson Heights, having come from someplace else, sleeping and waking up to the sounds of languages from corners of the world he had never even heard of—nothing like those advertisements in Life magazine at all. Some days, most days, better.

The dog’s hind leg kicks, and her lips flap; she’s dreaming. He looks out the window at the small, empty fenced-in run where there’s real grass for the horses, not like the artificial turf they have on the other side for the dogs. Nineteen years, almost all of Tess’s life. That’s how long he’s been working here at the airport, the same one he flew into when he himself came to America. As though he’s forever arriving. He follows the ascent of an airplane, thinks briefly of Mary again, and the kiss, then opens the e-mail from Minnesota for what seems like the hundredth time.

It begins: Dear Mr. Park, You don’t know me, and it took me a long while to find you, but I thought you might be interested in this photograph. . . .

He almost didn’t click on the attachment, a part of him worried that it was malware, but the sender mentioned his father’s name. He looks across at the dog still dreaming, and then he clicks again on the attachment and there he is, his father, in uniform, beside the sender’s father, a pale, blond white guy also in uniform, and they are somewhere in Korea, during the war. It could be a base, or it could be near a battlefield, who knows, but it’s sometime before shrapnel will rip across his father’s thigh, like a burning star, almost severing his leg.

But that’s not what made Roger catch his breath—that his father is not yet wounded. It’s that in the photograph, between the two young men, each on one knee, is what must be a military dog, wearing a vest, tongue out and grinning. His father’s hand is on the dog’s scruff, and his father, too, is grinning.

The photograph came yesterday. He hasn’t told Tess. Unsure, truthfully, what he would say: My father hated animals, and hated that my job was to care for them, and hated that I left him to come here to New York, and hated just about everything, including the fact that he survived, but here’s a photo that tells me otherwise, don’t you think?

He wrote back to the sender this morning, wanting more information about the dog, but he has yet to hear from the man again. He spent an obscene amount of time trying to find information on working dogs during the Korean War. Maybe it was a joke—the photo, that is. Maybe the dog was a stray the soldiers found and dressed up to have some fun for an hour, to keep sane for an hour in the insanity they were living in.

What say you? he murmurs softly to the dog in front of him.

He likes to imagine their reunion, the translator and his dogs. Even after all these years, it never fails to move him, the greeting after a long time. Maybe, if Roger gets to meet the man, he’ll mention the area where Tess wants to end up, near her college. He has been up there only once, the time he took Tess on her first day. He remembers getting lost after dropping her off, because he has never been good with directions, and he ended up crossing a bridge over the river and seeing the vastness of the valley. He was suddenly filled with a desire to keep driving back and forth over that bridge, to stay there, high above, forever.

In the moment that his in-box alerts him to a new message, he spots Tess outside, holding Ramsey’s lead, the two of them in the paddock, and then Roger jumps up or—as though he, and not the dog, were the one lying on the bed—sees himself jumping up from his chair at the same time that Ramsey rears, his front hoof catching Tess’s chin like a boxer’s uppercut.

Gwisin

The sister dreams of looking for her brother. Because she doesn’t know where her brother is, and where she herself is, it is in her dream that she navigates this new place, unbothered. She trots past a room full of birds in their cages who call to her and tell her to hurry. Past a man wiping another dog’s piss off the shiny floor. Past another man watching something on his phone and then past a small, narrow room with two cats in open cages who drop low to the ground as she eyes them.

In an empty, sunlit room, she enters a forest. She navigates the trees and the foliage into a clearing where her owner is sitting on a chair, watching television, and she hurries over, nudging him, and then gets distracted by the water bowl beside his feet, because she is so thirsty.

So the dog drinks and drinks, ignoring the horse approaching her and the sound of another airplane, this one pulling up to a gate, having touched down in the city where Brian’s mother was born. Mary hasn’t slept, because she was a little afraid to, not wanting to be there by the escalator again. And because somewhere beyond customs waits a girl who has a part of her ex-husband inside her, which means she has part of Brian, too, inside her.

Mary wishes she could see herself in a mirror before entering the terminal. It feels great to stand, even if the passengers are all bumping into one another, waiting to exit, the boy who slept almost the whole way beside her accidentally grabbing her hand and not his mother’s. She imagines the two kids meeting one day, her ex-husband’s daughter and their son, and she thinks, as she has done for days, of everything that could possibly be in the box, as though a small box like that could hold everything. As though he’d been the kind of man who would’ve saved something of hers, if in fact it is something of hers.

She sees him again, much younger this time: they’re walking down a sidewalk in the city past the enormous building that will one day be a shopping mall, and they’re shy with each other, physically, but can’t seem to stop talking. There is a softness to him on that day that she has no idea will vanish, replaced by the violence of him striking her and striking her, but she remembers this: that they couldn’t stop talking to each other in their first year.

She remembers this as the cabin door finally opens and the passengers begin to disembark, and as, thousands of miles away, back in New York, Tess decides that Ramsey needs some air and grazing time, and so she slips on the lead and takes him out of the Animal Center toward the paddock.

Tess wonders if she was in the wallpapered room too long. She’s groggy. As if a ghost is pressing down on her head and another is pulling on her waistband as she tries to walk forward with Ramsey behind her right shoulder.

She ignores the almost violent sway of his head because in that moment she cannot remember the Korean word, or many words, for “ghost.” To her surprise, this upsets her greatly. It becomes a pulse deep in her chest. And then it becomes an absence, as if she’s lost some part of herself, as if some part of her just fell out while she was walking. She reaches into her back pocket for her phone, wanting to call her mother, and then realizes she’s forgotten it in the room, and she begins to cry.

She opens the paddock gate, guides Ramsey in, undoes the lead, and cries, unaware that Ramsey, from the angle he’s standing, cannot see her—Tess has vanished from his sight—but he can hear her, can hear her upset, and it confuses and frightens him, and he rears.

It’s so fast Tess doesn’t feel it. When she opens her eyes, she is on the ground in the paddock, her father looming over her, blocking the sun, asking if she is all right. And she blinks. He asks again. She looks for Ramsey, who is licking his hoof, and she covers her stomach with her hands. She tastes some blood in her mouth and says, Gwisin, gwisin, gwisin.

The Spot

A few minutes earlier, on the opposite side of the facility, Brian stands by a trash can in the hallway. On the top is the foil-wrapped sandwich he made this morning. He picks it up, holds it, and looks around. A co-worker rounds the corner with another dog and nods, saying that it is beautiful outside.

It is beautiful outside. Carrying the sandwich, Brian heads back to the suite he has been sitting in, where the food and water bowls remain untouched. He tries the slip lead one more time over the dog. The dog steps back, head lowered.

If I put this on you, we can go outside, Brian says. He says the word “outside” again, more slowly, and he thinks the dog understands him; the dog steps forward into the loop of the lead, and they step out into a turfed area, entirely fenced, with a view of the pond, where there are no geese today, and, farther beyond the airport fence, the spot beside the public road where Tess often parks the car so that they can have a cigarette before going home.

He unleashes the dog, who makes a zigzag path across the turf, sniffing it, then follows the perimeter of the fence. Brian unwraps the untouched sandwich. He takes a bite. He says to the dog, I don’t know what her problem is, but this is delicious.

He pets the dog and tries to smile, but something has caught inside him that makes him uncertain about the rest of the day, as if everything has gone blurry, out of focus. He rubs the side of his face and tries again to remember his father. He remembers instead that there was an elevator repairman who sometimes worked in their apartment building in Jackson Heights and was kind to him, and he wonders where that man is now, and whether he’s still alive. He remembers the headlamp the man used to flash to make Brian smile before he vanished into the bowels of the shaft.

He remembers that the dog understood “outside.”

Before he is aware of what is happening, the dog’s mouth is over the sandwich, licking it at first, and then taking a bite. Brian laughs. It’s the first time the dog has eaten since he’s come here. There’s paprika in there, he says, so careful.

But the dog isn’t careful. He eats fast, tasting the paprika but not caring. He tastes farmland from the chickens who laid the eggs. He tastes foreign water and tinfoil and this man’s hands, which pressed the sandwich down. It all tastes good, the food, and, as he eats, a part of him returns from the journey he has taken to wherever he is now. He smells cleaning chemicals and the fumes of airplanes and cologne, that bird carcass somewhere near the pond, and he eats the rest of the sandwich.

Then he sits beside this stranger who he has not yet decided is a friend and considers the way the young man stares out at a spot behind the pond with an expression that seems like anticipation or longing of some kind. As if it is the spot where this young man will find an answer to something he has been questioning, and the spot where at long last the dog will find his owner who has been waiting for him all this time.

The dog imagines leaving this unknown place, slipping past the fence, taking with him his sister, whom he can still hear, in a corner room in the building behind him, dreaming, the way he can hear birdsong and other dogs and a vacuum and horses and music from headphones and the notification sound of a computer and a man’s faint shouting and a woman saying a word he doesn’t recognize.

What he can’t hear are the passengers waiting for their flights in the main terminals or the people getting ready for their shift at a restaurant in Jackson Heights or the cows on a farm in upstate New York or Mary’s reaction when she opens a box and looks inside or the door to his old home crashing open and his owner, who worked as a translator for the Americans, being dragged out by three men who force him to lie face down on the dirt road as they shout that he’s a traitor and then fire a rifle at the back of his head.

He cannot hear any of that. He fixates on the woman in the grass on the other side of the building saying that word again as she is helped up. He waits for her to say something else. He waits for his sister to wake. Staring out beyond the pond, from where a breeze is approaching, his belly full and this young man’s heart beating loudly beside him, he waits for his name to be called. ♦

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.