On a Saturday afternoon in early July, the clouds blackened above Hampton Court Palace, southwest of London. Crowds gathering for the Royal Horticultural Society’s Hampton Court Palace Garden Festival on the sprawling palace grounds reached into backpacks for umbrellas with the resigned look of people attending a supremely English occasion designed to be held in sunshine. We go on being surprised by the weather in England, though it has never given us cause for hope.

At one of the many festival stands, Clare Lenaghan-Balmer, the head of marketing at Henchman, a company that makes high-end ladders, had the air of someone cheerfully awaiting the apocalypse. At 2 P.M., Lenaghan-Balmer—wearing both a fleece and a raincoat—was due to announce the winners of Henchman’s inaugural Topiary Awards, a competition to find the finest topiarists in the country. The idea for the awards had occurred to her after years of hearing about Henchman clients’ elaborate back-garden creations. “People would tell us about these masterpieces,” she told me. “But no one ever sees them!” Also, it was a good marketing ploy for a ladder company; as far as she knew, no one in England had ever held a topiary competition.

After launching the awards in March, Lenaghan-Balmer received more than seventy entries in two categories: home gardener and professional. Photographs submitted by contestants revealed topiary everywhere from suburban hedges to the expertly maintained acreages of stately homes. Britain is a nation of hedges, after all. A series of parliamentary enclosure acts, which intensified in the seventeenth century, transferred much of the country’s land from common to private ownership, its boundaries fenced and hedged. The full length of Britain’s hedges is estimated to be nearly half a million miles, more than its roads.

Lenaghan-Balmer was delighted by the photographs she saw. Among the entries were a tractor, two dogs, and a vast, smiling frog, which had been tightly clipped out of boxwood. The topiarists themselves included a dog groomer who’d transferred her skills to clip a topiary peacock and a professional gardener who’d spent a decade cutting his hedge into the shape of the New York City skyline.

A topiary is not made overnight. The plant, typically boxwood or yew, can be shaped year after year as it grows. The topiarist will use sharp long-handled or electric clippers, or, for the specialist, lethal Japanese shears. For topiary enthusiasts, the obsessional commitment and long-term vision that the practice demands are part of its appeal. Yew can live for a thousand years or more: topiaries, like children, often outlive their creators. Earlier this year, residents of Bishop Monkton, a village in north Yorkshire, were distressed when a thirty-foot topiary cockerel in a cottage front garden was suddenly felled by the home’s new owner. The cockerel had grown for more than a century, present for the comings and goings of the village, its births and deaths. The villagers wished that they’d at least been consulted, the local news site, Bishop Monkton Today, reported.

At Hampton Court, as the rain began to fall, one of the competition judges arrived: the ebullient Elizabeth Hilliard, the editor of Topiarius, the official magazine of the European Boxwood and Topiary Society. Undeterred by the weather, Hilliard wore a floral dress, a pink coat, and a bright smile. She is an unmatched topiary enthusiast, and had been impressed by the standard and range of entries. The photographs had proved a theory she holds that topiary, sometimes dismissed as a quirk of questionable taste by more high-minded gardeners, has been enjoying a resurgence. “There was so much determination to make joy and delight, one way or another,” she told me.

A couple of weeks before Hampton Court, Lenaghan-Balmer had tipped me off about the leading contenders in both categories. The standout professional was a topiarist named Harrie Carnochan, who maintained an immaculate formal garden at Pitshill, a neoclassical mansion in West Sussex. As for the home gardeners, there was one I had to see. A man in Aberdeenshire, in the northeast of Scotland, had created a spectacular topiary display in his garden from some yew saplings he’d planted some forty-five years ago. Lenaghan-Balmer sent me a few photographs. Cut out of the hedge was not a single shape but an entire series, including a whale, two sharks, a cresting wave, and a boat with a man standing on deck, forming an extensive tableau from “Moby-Dick.” Their creator, a seventy-four-year-old named David Hawson, had written an accompanying description: “The gentle curve of a wave touches the stern of Captain Ahab’s ship, the Pequod, on the deck of which stands Queequeg, the highly tattooed South Pacific islander who is poised ready to harpoon the great white whale from whom appears a spout of water as he prepares to dive.” Even for topiarists, it was extreme. Lenaghan-Balmer was thrilled: “It’s absolutely insane.”

Topiary in the form of smiling frogs and multipart “Moby-Dick” reconstructions can seem like an advanced case of English eccentricity, veering close to other, equally aestheticized and particular national pastimes, such as dressage and competitive dog shows. The royals and the aristocracy in England set the trend: some of the oldest topiaries in the country are the massive sculpted yew trees at Hampton Court, once the palace of Henry VIII. Today, King Charles III is renowned for elaborate garden projects at various of his houses, including a new topiary garden at the Norfolk estate of Sandringham. (This year, at the Chelsea Flower Show, alongside show gardens themed around forest bathing and Netflix’s “Bridgerton,” a major attraction was the unveiling of sculptures of the King and Queen’s terriers, Beth and Bluebell, woven out of willow.)

Topiary, however, is neither exclusively nor originally English. The Romans topiarized, as seen in the letters of Pliny the Younger, in which he wrote of animals, figures, and, embarrassingly, the letters of his own name cut out of boxwood at his Tuscan villa. Formal gardening enjoyed a revival during the Renaissance and thrived as a performance of wealth and power in France and the Netherlands in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Today, contemporary Japanese cloud gardens are revered by topiary fans. America has its own offerings, too, such as the Topiary Park in Columbus, Ohio, populated by figures from Georges Seurat’s painting “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte.” The French have the historical edge, at least of topiary in its most exacting forms, with the grand formal gardens at the Palace of Versailles and swaths of rounded, bubbling topiary at the gardens of Marqueyssac. Topiarius is written in both English and French, and it is the French membership who set the tone at society gatherings, Hilliard said. As soon as the music started at a recent party, she told me, “the entire French aristocracy were grooving away.”

Still, the Brits, as ever, claim longevity. The self-proclaimed “oldest topiary gardens” in the world is at Levens Hall, in the Lake District, cared for by the head gardener, Chris Crowder, the eleventh person to hold the job since the garden was created in 1694. Fashions changed shortly thereafter, with formal gardens replaced by naturalistic parkland made popular by the eighteenth-century landscape designer Lancelot (Capability) Brown. The garden at Levens Hall, left intact, was allowed to grow into a population of around a hundred abstractly shaped topiaries, like a very mixed crowd at a garden party. Crowder has spent much of the past thirty-odd years clipping them into shape. To tell them apart, he has given them nicknames: Homer Simpson, Darth Vader, R2-D2.

Some fifteen years ago, Crowder decided to make his mark on the garden and planted some yews. He alone is allowed to tend them. “I wouldn’t want anyone to mess with my babies,” he explained. A sense of quasi-parental ownership is common among topiarists. “Every person is like his topiaries,” Todd Longstaffe-Gowan, an eminent English garden designer, told me. Spend long enough tending a plant and it starts to reflect your personality. Every gardener, like every parent, has their own style: there are those who allow their topiaries to grow into abstract forms or elephants, and those who prefer precisely measured triangles arranged in ruthless symmetry.

At Pitshill, Harrie Carnochan, the favorite to win the professional category of the Topiary Awards, had sculpted neat rows of holm oaks into perfect spheres and shaved symmetrical yew and boxwood hedges until they were hard-edged walls. Striving for perfection was a draw of the job, Carnochan told me. Oaks and yew would naturally grow into huge trees, the kind you can walk inside, great cathedrals of leaves. “We’re trying to control them,” he said. “I do like that side of things.” In any case, a vision of tamed nature is evidently the desire of Pitshill’s owner, Charles Pearson, the younger son of the Third Viscount Cowdray. (In “The Topiary Garden,” a children’s story by Janni Howker, an old gardener complains that his working life tending topiaries has been spent “turning what’s natural into what’s unnatural, just for the pleasing of a gentleman’s eye.”)

But no garden is quite what it seems. Capability Brown’s “natural” landscapes were feats of engineering that took years to build. (To create the lake at Blenheim Palace, Brown’s workers had to dig out, flood, and then dam an entire valley.) To create a wildflower meadow today, Hilliard reminded me, usually requires extensive design and costly work to manage native weeds that, left to their own devices, would take over. Topiary, on the other hand, might appear artificial, but, as several topiarists expressed to me, if not too tightly clipped, it can provide an evergreen refuge for birds and their nests. As with people, wilderness can lurk beneath the neatest of exteriors.

About half an hour from the coastal Scottish city of Aberdeen, the roads gradually narrow and wooded hills rise. After turning a sharp corner, I found myself driving alongside a parade of green creatures, including the “Moby-Dick” magnum opus and enormous sculptures of a man and a woman, cut out of yew. As I pulled up to the accompanying cottage, pretty but utterly upstaged by its hedge, I was met by smaller versions of the topiary man and woman: David and Susie Hawson.

David Hawson—who has the slim, stretched look of a silver birch—planted the hedge not long after he and Susie moved into the cottage, in the late nineteen-seventies. Cattle from the neighboring farm kept wandering down the lane and into the garden. They needed a barrier but didn’t want a fence. Hawson was the local doctor, Susie a nurse: they spent their lives tending to the local community. Fences, they felt, were a visual statement: “Keep out. We’re not that kind.”

Hawson is a different kind entirely—a man driven by a never-lost childish thirst for fun, with a polymathic array of enthusiasms, including electrical engineering, fishing, painting, collecting old records, and making time-lapse YouTube videos. As his yew saplings grew, he found himself seeing things. “What happens,” he told me, as we sat at his kitchen table, “is that you get little bits that come up—I call it a ‘sprong,’ a bit that’s uncut—and you look out the window and you think, Oh, that looks a bit like a whale. And then I thought, If it’s a whale, well . . .” He paused to announce the logical next step. “I read ‘Moby-Dick.’ ”

Hawson went on to make the Pequod, the sharks, and Queequeg during the next decade or so. He was particularly proud of his wave. “I like the splash of water where it comes out. It’s not static and square,” he said. “A lot of topiary is very geometric.” After the completion of the “Moby-Dick” sequence, he remembered a painting he’d liked at the Aberdeen Art Gallery of a girl and some geese. “But I couldn’t do the girl, so I decided to do British species of birds.” In the course of several more years, he made a blackbird, a robin, a cockerel, a tawny owl, a pheasant, an osprey, a long-tailed duck, a goose, and a roly-poly bird (a fictional character from the work of Roald Dahl).

The topiaries of himself and Susie, which came later, were born of a misunderstanding. A woman was passing by while Hawson was up his ladder, wondering what to do with an unclipped part of the hedge. He asked her what she thought it might be. The woman took a sprig between her fingers and said, “It’s yew.” “Of course it is!” Hawson replied, and he proceeded to shape a monumental self-portrait with an outstretched arm, as if gesturing proudly to his creations. He calls it “Me in Yew,” certain that his topiary pun is unique.

As we walked around the garden, Hawson variously described his forty-five-year topiary project as a “giggle,” something distracting to do while he was on call as a doctor, and a pleasing if labor-intensive way of making people smile. “I defy anyone to go up the road seeing it for the first time and to remain glum,” he said. With the self-deprecation of a certain kind of Brit, for whom the greatest crime is to be seen to think too highly of oneself, Hawson insisted that he knew nothing about gardening. Instead, the urge to sculpt hedges was related to his love of painting. After he stopped working as a doctor, he’d decided to devote more time to art, but even that seemed to run the risk of pretentiousness. “Artists sometimes take life awfully seriously, and I don’t really,” he added. Hawson showed me other garden projects to prove his point: a tree growing through the middle of a bike frame that he’d placed over it as a sapling; a ninteenth-century railway carriage, which he’d fitted out with an electric train that ran around a track on a shelf just below the ceiling; a Second World War field telephone that he’d installed in the carriage and wired up to an old-fashioned red telephone box by the road. When passing drivers pulled into the lay-by near the phone for a rest, he encouraged his grandchildren to bewilder them by calling the phone.

Then there was the rest of the topiary. An old box hedge running down one side of the garden had been turned into a procession including an owl, a pig, two rabbits, a hen, a goose, a duck, a snail, a dove, some Barbara Hepworth-style abstracts, and a basking shark. Until recently, there had also been a topiary cat chasing a topiary mouse, but a nearby tree had started dropping branches and killed the cat. He was waiting to see what the plant would remind him of next. “I think the principle of the kind of topiary I’m doing is to let nature suggest, and I will then help it on its way,” he said. “I don’t use any frames. I think that’s important.” He looked immediately embarrassed, as if to talk about the principles of topiary was absurd.

Hawson claimed not to be wedded to what he had made over all these years of clipping, mostly by hand. “The next person who takes on this house will be very wise to take a chainsaw to some of these things,” he said, looking round at his menagerie. I was surprised. All that work, just to be heartlessly felled like the Bishop Monkton cockerel? “I’ll be dead!” Hawson cried. “I won’t know about it!” As for the Henchman competition, he’d entered on a whim because he wanted the ladder. Did he think he’d win? “Oh, yes,” he said. “Oh, yes, oh, yes, oh, yes.” Hawson gestured toward the birds, the boat, Queequeg. “Who else has got that?”

At the end of May, entries closed for the Henchman Topiary Awards. The four judges then had to decide their winners based on the topiarists’ photographs. It wasn’t easy. One of the judges, the professional hedge-cutter and topiary influencer Andy Bourke—known as @the_hedge_barber on Instagram—told me that he liked to be able to walk around a piece of topiary to examine it from all sides. A photograph wouldn’t necessarily show you the ragged underbelly of a ball or the uneven sides of a pyramid. But the judges couldn’t travel the length of Britain, from Scotland to Sussex, to see it all for themselves. Bourke and the other judges were looking for the signs of a superior topiarist: a precise technique and a sensitivity toward the plant and its environment. The finest topiary contains a kind of contradiction: it should look clean and neat, meticulously clipped, but at the same time unforced. The plant should be healthy and shaped in sympathy with its natural growth, as if it had always wanted to become a frog.

In recent years, Bourke said, he’d noticed a surge in topiary’s popularity, though not necessarily in the long, slow art of shaping it. Wealthy clients, he said, often want the “wow factor” of a major piece of topiary without the investment of time. Instead, a topiary will be bought from a specialist nursery, and transported on a lorry with its thirty-year-old root ball wrapped up until it can be re-inserted in the ground. This has precedent: starting in the eighteen-thirties, the Fourth Earl of Harrington demanded that his team of gardeners (at one point, he had more than eighty) uproot and deliver established trees to his formal garden at Elvaston Castle, to which he would admit no one but his wife.

These days, one of the premier dealers of topiary in Britain is Paramount Plants, in the North London suburb of Enfield. Paramount has the usual range of lollipop trees and box spirals, which stand like sentries at front doors in London’s more expensive neighborhoods. Then there are the one-offs: a giraffe (£1,963), a prancing horse (£2,733), a fire-breathing dragon (£17, 325). “We don’t sell more than one a year of those,” Tim Terry, the sales manager at Paramount, said of the statement pieces, “but you do get the odd eccentric with money to burn.”

Most things are signifiers of class in Britain, and topiary is no exception. In the aristocratic social code where older means better and subtlety is king, the seventeen-thousand-pound topiary dragon commits the fatal crime of announcing wealth suddenly and loudly, a sure sign of it being recently acquired. Crowder, at Levens Hall, felt that the dragon-buying types were also missing the point of topiary, which is to tend to the plant yourself. “I suppose if you have a lot of money and not much time,” he said, mournfully, “it’s what you have to do.”

Also: a fire-breathing dragon? Hawson had spoken to me of the fine line between imaginative topiary and regrettable kitsch. “I sometimes worry I might have crossed it,” he added, but he did have limits. He would, for example, never clip a Disney character out of his hedge. (Disney World’s Epcot theme park, in Florida, has that covered, with topiaries ranging from Groot to Tinker Bell’s Fairy House Garden at its 2024 flower-and-garden festival.) To ward off potential lapses in taste, Susie will come round the garden and say to him, gently, “No, darling. Not there.”

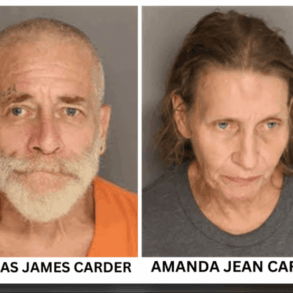

By mid-June, it was time for the Henchman judges to make their decisions. They were not allowed to confer, and didn’t need to. The winners were clear. Carnochan won the professional category for his “exquisite” precision at Pitshill. And in the home-gardener category it was Hawson, of course. “Just an utter joy,” Hilliard said, noting the curved wings of Hawson’s osprey, which looked as if it were about to take off into the sky over Aberdeenshire.

Hilliard liked, too, that Hawson’s topiary still performed the ancient role of a boundary. It kept out the cattle. Hawson’s hedge displayed a kind of freewheeling playfulness, a talent for making the functional beautiful but also ridiculous, which somehow enhanced its beauty. His cast of creatures, Hilliard said, “practically dance off the top of the hedge.”

At Hampton Court, at nearly 2 P.M., someone checked the weather app: the rain was due to pause for roughly twenty minutes. There might be just enough time to present the awards to the pair of winners before the next downpour. As the sun tentatively came out, Lenaghan-Balmer shepherded the two over to one of the nearby show gardens at Hampton Court—a more handsome backdrop than the Henchman display, which contained only ladders. Standing among picturesque grasses and pink flowers, Hawson and Carnochan were each given a small glass trophy and a flute of champagne, and required to pose for photographs with Hilliard, who was holding a copy of Topiarius.

Together, Hawson and Carnochan formed an odd couple. Hawson wore an English summer ensemble of cream linen suit and Panama hat that appeared to have walked out of an E. M. Forster novel. (His favorite of Forster’s novels is “A Room with a View,” whose Florentine vista he’d painted on an interior wall of the phone box in his garden.) Carnochan, in jeans, a checked shirt, and old trainers, looked like he’d just stepped off his ladder, the back of his neck the deep rust of a man who spends his summers snipping perfectly spherical balls of yew. Their work represented contrasting ways of managing topiary and life itself. Geometry versus art, restraint versus freedom, regimented control versus uninhibited expression. But all opposites have their overlaps. “I wonder if his back is as bad as mine,” Carnochan said.

As they chatted, Hawson and Carnochan discovered other connections. Carnochan’s brother lived a few miles from Hawson, and Carnochan had considered moving up that way. Not only that, but Charles Pearson, the owner of Pitshill, where Carnochan worked, also owned Dunecht, one of the largest private estates in Scotland, which was close to Hawson’s garden. A strange coincidence, until we remembered that a large proportion of British land, fenced and hedged, is owned by a very small number of extremely rich men.

Walking back to the Henchman stand, Hawson told me there was something he wanted to correct. In Aberdeenshire, he’d told me he wouldn’t mind if someone took a chainsaw to Queequeg and the rest after his death. Well, now he wasn’t so sure. Recently, he’d learned that a number of wind turbines were going to be installed on a hill near his house. He was worried that the trucks transporting their parts along the lane might damage some ancient oak trees and his hedge, and he’d put in a request to the council for their protection.

Hawson didn’t want to lose the topiaries, he realized. This wasn’t his artist’s ego talking, he promised. No, it was more that his creations had developed identities beyond the shapes he’d given them. People responded to them. When strangers drove down the lane past his hedge and stopped to admire it, he’d invite them in to see the rest of the garden. The topiaries brought people pleasure, and he’d like them to continue to do so, beyond the limits of his own lifetime.

Yew lives for centuries, gesturing both back and forward in time, far from our own short turn on the soil. But topiary does more than endure. In the hands of those blessed or cursed with the urge to sculpt plants, a topiary develops character. Like a child, it requires devoted care and insists on its individuality. Hawson, walking around his garden, had pointed out a boxwood pig that looked like it was emerging from the undergrowth beneath a hedge to one side of the driveway. “He appeared yesterday,” Hawson said, as if the pig had arrived of its own volition, a mystery of nature that might last a hundred years, shaped in passing by a human hand. ♦

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.