The sun dogs of a bitter January morning eerily followed alongside the truck filled with eight bird dogs headed for warmer weather. Louvered doors were pulled tight and taped to prevent the biting winds from reaching our canines. However, as we turned southbound on I-29 in South Dakota, the crosswind slithered its way in, plummeting the temperatures in the box near zero. Normally, a reprieve from winter can be found within a few seconds, minutes, and degrees south; but that wasn’t the case this time. Below zero temperatures gripped the Midwest from the Canadian border down to our quail country destination. An hour at those temperatures is one thing, but fifteen hours is a completely different challenge. Doubling back, my fellow hunting companion George Lyall and I decided to forgo the camaraderie of a good road trip in lieu of our cargo’s well-being. Back on the road, we cursed over the phone about the hair slithering its way into the very foundation of our trucks from the back seats.

Advertisement

We climbed over the snow drifts adorning the parking lot of the southern Kansas no-tell motel and opened the door to find the snow too was seeking shelter from the unforgiving landscape. All eight dogs sprawled out on their backs across the room, savoring their rare treat. We spoke of the upcoming trip with the eager anticipation known best to hunters, imagining and conspiring with the same fervor as when one dreams of a statuesque pointing dog, poised and signaling the presence of a covey of bobwhite quail. The excitement mirrored that of a farmer or other wise men who know that rain brings life to the lands.

Bobwhite Quail Trends in the Midwest

Bobwhite quail population trends across the midwest (Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas) go hand in hand with moisture, and the early summer precipitation of 2023 gave those who pursue them something to talk about. Looking back, 2014-2016 was the last time quail populations roared back with a vengeance. If you were looking at the populations with a bar graph, there was a good blip in 2014, followed by 2015 where it rose again, and nearly doubled by 2016, signaling the best quail numbers in a decade. If you were a bird-dogger in those years, life was good. However, these fat times were closely followed by some of the lowest numbers in the past 30 years. The 2023 season was different with early whispers of rain, but an abnormally hot and dry summer tempered many expectations. However, could this season be a similar blip seen in 2014?

Advertisement

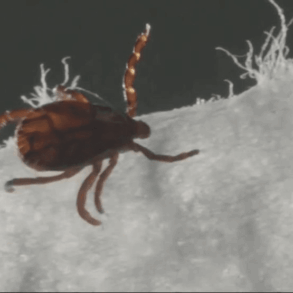

Historically, quail populations in the midwest are highly sensitive to weather patterns, with rainfall playing a critical role in their breeding success and survival. In years of ample precipitation, the landscape blooms with vegetation that provides cover and food, supporting higher quail numbers. Conversely, drought conditions can lead to sharp declines, as lack of cover and food diminishes their chances of survival and reproduction. This cyclical nature of quail populations makes every hunting season unique and unpredictable.

As we sat sipping on our beer in the swiveling office chairs, talking through the interior doorway adjoining the motel rooms, we reminisced about the good years. George regaled the room full of dogs with the story of having to lead his prized pointer, Tucker, out of the field after finding well over thirty coveys in a walk, afraid he’d collapse. I had heard the story countless times at this point, but the optimism and bright-eyed hope emanating from the rural Kansas motel was contagious. Even the seasoned black-headed bird dog, now in his eleventh year, perked up at the vivid retelling of his remarkable performance.

Fueled by the hours of endless lines in our wake and just enough light beer, we drifted into a slumber with the promise of the days ahead. By the following afternoon, the miles began to accumulate beneath our feet, and the once hopeful anticipation gave way to a melancholic, almost mechanical routine as we laid our vests on the tailgate, gazing out over the vast Oklahoma prairie.

Advertisement

Hunting Bobwhite Quail in Oklahoma

The rain had certainly reached this part of Oklahoma as the grass formed mats, blanketing the entire ground. While this may be good for pheasants, it doesn’t bode well for quail. Their preference is for 30 to 60 percent bare ground, making it easier for them to move about on foot. After a few hours of driving in search of a better option, we pulled out a trick I’ve learned to utilize more readily. Within the hour, we had packed our bags and pointed the truck southward. I’m sure our armada of bird dogs could have unearthed enough birds to salvage the trip, but oftentimes, hitting for singles gets in the way of triples and homers. I would have guessed we had crossed the southern Oklahoma border into western South Dakota as the prairies sprawled in all directions. One of the only telltale signs were the red dirt roads wish boning off the pavement.

We met up with a fellow cover dogger from the north country, Bert, and his bird-dog-crazed hunting buddy, Amy, who is from Oklahoma City. She has fallen in love with all things upland, and with our tremendous amount of dog power—numbering well over fifteen—we hit the field. As we met them at the gate, our trucks spooked a covey of birds, their rapid explosion pegging our “pumped meter” to ten. We opted to let that covey settle down as we pushed through a tree grove. When we finally were able to train our gun barrels on the first birds of the trip, all it took was a nice piece of dog work for all the miles to be forgiven. The mojo was back, and as the pointers and setters gelled, cohesively working the shortgrass prairie, the wash of nirvana floated in on the north Texas wind.

Hunting Quail in Texas

Unlike our previous location in Oklahoma, this particular area had received just enough rainfall throughout the summer to sustain the young chicks over the hot summer months. If you’re looking on a map of historic rainfall, finding areas that have increased precipitation can make the difference between a banner day and zeroing out. The area we were hunting in had a swath of rainfall only 30 to 40 miles wide come through in August, giving a life-sustaining influx of moisture. That’s the only difference between it and the area we had hunted in the days before.

We drove through a depression, approaching a fence leading us to our next location, and I felt the tires sink under the weight of the heavy 3⁄4-ton truck. Mud, and a lot of it. In the weeks past, there had only been a scant amount of rain, and certainly not enough for tires to be coating the side of my truck in mud. We soon found the culprit: an overflowing cattle tank sending water branching out like arteries into the Texas soil. Whether the water was delivered by the clouds or by other means, it bodes well for the quail. We dropped the dogs, paws tearing up the dirt as the two setters, shorthair, and pointer broke away.

Within 200 yards, Bert’s setter caught the familiar scent of quail, freezing in her tracks. Instinctively, the other dogs stacked behind her like cordwood. As Amy and Bert drew nearer, a robust covey of quail took to the air, rising in their distinctive, scattered formation. It looked like a couple of wizards waving their wands in the air as shots harmlessly passed by the fleeing birds. Finally, Amy’s last shot connected with a lone cockbird, and her shorthair bore down on the downed quail. The sun sank towards the horizon, and we made our way back to the truck, giving the birds time to covey up before the evening’s temperature gripped the plains. We approached the trucks, but not before the old pointer, Tucker, slammed into one last find before calling it quits. I sat on the hillside, petting my young setter and watched it unfold as the veteran bird dog stood statuesque. Just like countless finds before, the birds lay at 12 o’clock off his nose. George deftly sent a lone bird to the ground as I turned and made the short walk back towards the truck. Night fell as we divided out each dog’s respected portions, and as they enjoyed their nightly meal, we toasted a successful day. We had one more day before heading back to the inclement weather of the north, and we had a good one in store.

As it happens, we were only hunting a short drive from Steve Snell, owner of Gun Dog Supply. Steve has a wealth of quail knowledge and serves on the board of directors for Rolling Plains Quail Research Foundation. He has been hunting this area for decades and has experienced the population swings firsthand. Similarly to talking about the weather, the subject of quail populations came up and I could tell Steve was cautiously optimistic about the future. Approaching one of the seemingly countless doors on his chassis-mounted kennel, he collared a dog, and we headed off into the sandy hills. This lease was intensively managed strictly for quail, and Steve was much more interested in putting his string of young dogs in front of them than actually shooting them. The unpressured birds behaved like true gentlemen and didn’t wander off the nose of his young pointer. However, they flushed at the perfect instance and headed in the exact correct direction, sparing them from our loaded 28s. We didn’t have to wait long as Amos, my three-year-old pointer, locked down another covey. This time, the birds traveled in a perfect left-to-right motion, and the swing of my barrel was true, knocking down a lone Bob. We continued making short loops in different directions, ending back at the truck to ensure we were able to make it through our stable of dogs.

As we crested each hill, the endless prairie stretched before us, fueling our desire for one more round. Unfortunately, it was time to call it a day, and we left wanting more. The southern prairies await, and whether they hold 30 coveys or just a few, I’ll be doing a raindance in hope for the former.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content.